Cheap exports deliver deflation as Beijing looks for ways to spread its economic pain

(Originally published March 4 in “What in the World“) As China’s leaders convene this week to discuss remedies for the nation’s plight, the world may be about to get a taste of China’s economic downturn.

With fleeing capital and diminishing growth pushing its currency lower and lower, it was only a matter of time before China gave in to the urge to use exports as a beggar-thy-neighbor stimulus plan. That moment has apparently come. Chinese companies are flooding global markets with cheap cars and gadgets domestic consumers won’t buy.

The same thing happened back in the late-90s and early 2000s, but in those years China’s economy was booming, so its export surge was offset somewhat by booming imports of raw materials. That isn’t likely to happen this time.

As explained in this space last September:

A weaker yuan helps China’s exports, so the falling yuan will make those slumping U.S. dollar trade revenues go further back home in China. Indeed, August exports denominated in renminbi fell just 3.2%. More troubling for the rest of the world is that China’s weakening economy is hurting its demand for imported goods. China’s imports in August fell 7.3% to $216.5 billion as consumers cut spending in the face of weak job growth and falling property prices that threaten to bankrupt China’s heavily indebted developers.

Not that China’s factories are pumping out good any faster. On the contrary, China’s official gauge of factory activity showed a fifth consecutive month of declines. The purchasing managers index for February came in at 49.1, down from 49.2 in January. Anything below 50 in this statistic represents a contraction.

Faced, meanwhile, with complaints that its laws against espionage were so vague and broad that ordinary businesses are being paralyzed by fear their market research might constitute spying, Beijing has acted to make another law even broader and vaguer.

The National People’s Congress last week passed revisions to China’s Law on Guarding State Secrets, adding “work secrets” the list of information that is unlawful to not keep secret.

The latest revision is being cast as a new effort by Beijing to restrict foreign businesses in China. Last July, China introduced a new Law on Foreign Relations that created a legal basis for Beijing to impose the kind of extraterritorial commercial sanctions Washington imposes to enforce its own foreign policy on companies at home and abroad. Analysts reviewing the new law, however, said it is so vague that it adds to the risk and uncertainty already troubling foreign investors about doing business in China.

The new law followed crackdowns on foreign consultants for alleged espionage and on the dissemination of financial data offshore. Last April, China revised its Counter-Espionage Law to stipulate that all “documents, data, materials, and items related to national security and interests” were tantamount to official state secrets, without offering a clear definition of what would constitute “national security and interests.” The revised law empowered authorities to seize “data, electronic equipment, information on personal property” and to stop people from entering or leaving the country as part of any investigation into violations.

Foreign businesses say they now can’t tell what economic data, market research and other financial data in their possession might end up falling afoul of the law. The confusion echoes the uncertainty following China’s passage in 2016 of a broad Cybersecurity Law that prohibited the export of any sensitive personal data on Chinese individuals. Ironically, U.S. President Joe Biden issued a similar prohibition this week in the stroke of a pen through an executive order.

One piece of economic data that might give them further pause is the level of nonperforming loans that have been shifted from China’s banks to financial markets. Japan, the expert on how a property crash can send an economy into a coma, just issued data warning that China’s efforts to clear bad loans from its banks may be simply spreading default risk around, in much the same way the mortgage-backed securities spread risk from the American housing market from banks to investors ahead of the Lehman crisis in 2008.

Here’s how: China’s banks have loaned too much to property investors, many of whom can’t or won’t repay their loans. Banks have to set aside capital against these nonperforming loans, which is money they can’t lend out for new businesses that do repay. That strangles the economy, so the prevailing solution is to either encourage banks to write down those NPLs and take losses, or if doing that would push them out of business, sell some of those NPLs at a discount to healthier banks or to special companies set up to buy them, called asset management companies.

Another way to offload these bad loans is to cut them into slices, and package the slices into a bond, then sell the bond to investors. This process, called securitization, has several advantages. First, it ostensibly reduces the risk to the buyer that the security goes bad because a single borrower defaults. Second, that lower risk can translate into a lower interest rate for the seller, a bank, to pay. Third, it multiplies the market of buyers for bad loans by creating a smaller product for investors who don’t have the capital sufficient to risk buying a huge block of nonperforming debt.

But the problems with securitizing debt are now glaringly obvious. As we learned in the global financial crisis, securitizing debt may reduce the risk of a single borrower defaulting. But if all the borrowers default, then the securities backed by those loans also go bad. That means if there’s a market-wide property slump, these loan-backed securities are arguably as risky, or even riskier, than buying a loan on a single property. And China’s securitized NPLs are backed by loans that are already in trouble—in the middle of a nationwide property slump. So, trouble.

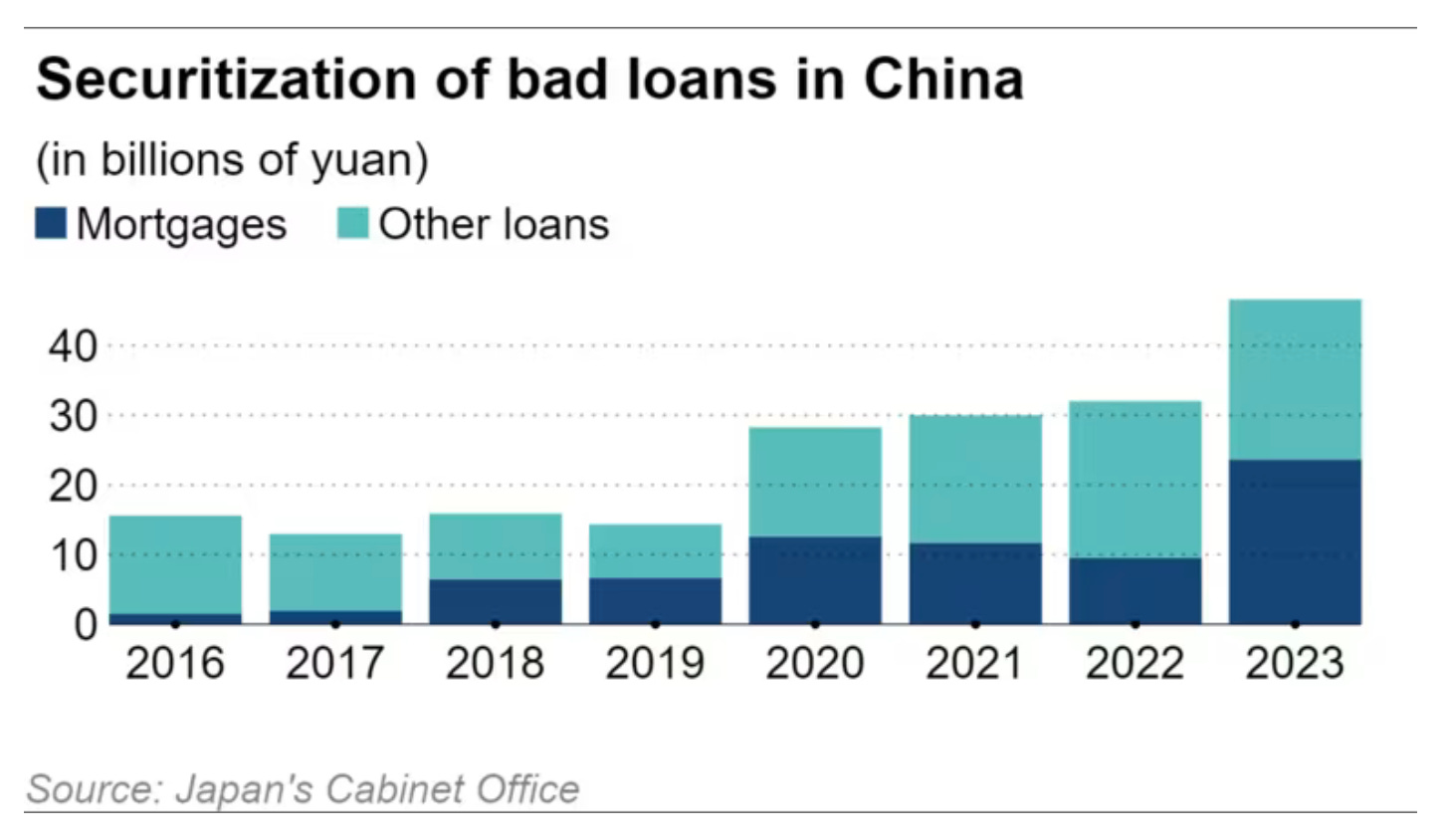

What Tokyo is disturbed by is how fast China has been trying to shift banks’ NPLs into the wider market using these securities. Sales of NPL-backed securities rose 46% last year, according to a report from Japan’s Cabinet Office, to 46.6 billion yuan ($6.5 billion), from 32 billion yuan in 2022.

And the loans underpinning these securities look increasingly shaky. China’s property morass and its risks to China’s economy are well-publicized. As prices fall, property developers and local governments face insolvency. Yet the overhang of property loans is massive: property loans outstanding are equivalent to almost 42% of China’s GDP, more than double the 20% Japan saw before its own property bubble collapsed in the early 1990s. And roughly half of China’s NPL-backed securities are backed by nonperforming mortgages.