As tariff threat looms, China claims 5% GDP growth despite shrinking population

(Originally published Jan. 17 in “What in the World“) China says its economy grew 5% last year even as its population continues to shrink.

China’s published GDP growth for 2024 magically attained Beijing’s official target, even though it ranks as one the slowest rates in decades. It’s even more fantastic when considered against the fact that the National Bureau of Statistics also revealed Friday that, thanks to a record low birth rate, China’s population shrank in 2023 by 2.08 million people, or 0.15%, to 1.409 billion.

And more of those remaining Chinese are joining the ranks of economists who don’t buy the government’s GDP data. As explained in this space last summer, economists have long suspected that China’s GDP data may involve more art—and politics—than science:

For years, economists noticed that China’s provincial GDP numbers, when combined, added up to a national economy that was bigger and faster-growing than what Beijing was toting up. The reason: Provincial officials’ own promotions in the Communist Party depended on their economic performance, so they were embellishing their numbers, sometimes subtly, sometimes fantastically. Small exaggerations to GDP in one province added up to a big discrepancy at a national level.

And Beijing’s own GDP reporting has also tended to raise eyebrows among economists. Even in quarters when it was clear to anyone with eyes that growth was stumbling, the economy’s official performance would come in at or near the official target.

Eventually, economists have come to look at China’s GDP numbers as a narrative, like many on TV, “based on a true story.” They may not be spot on, but they are at least “directionally accurate.” Why not just ignore them, then? “Because there is no authoritative alternative.” And at the end of the day, economists must rely on data from somewhere to do their jobs.

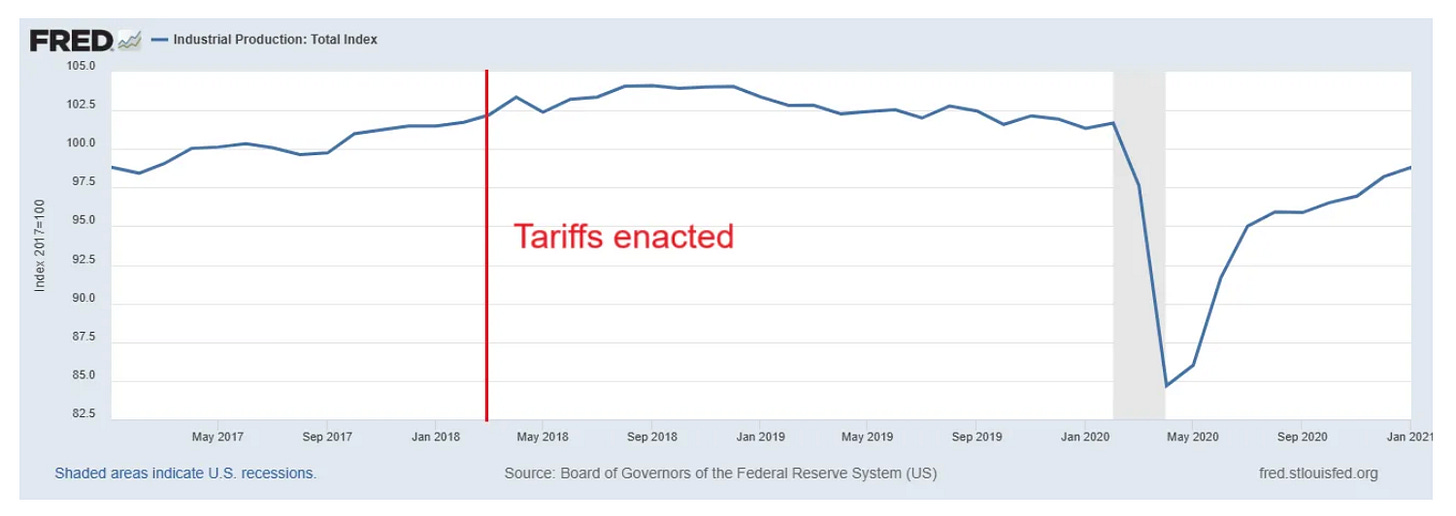

Economists and the International Monetary Fund have long urged China to wean itself from the old “capitalist developmental” model it adapted from Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan and instead stimulate domestic consumption. Easier said than done. Economist Noah Smith devotes 4,100 words of his latest blog to pondering China pundit Michael Pettis’ argument in a recent piece for Foreign Affairs that Trump’s threatened tariffs would help force China to rebalance toward domestic consumption—while forcing the United States to rebalance away from imports. After 3,300 entertaining words, Smith reaches the point you already know about tariffs: factories are too big and expensive to move in response to them. As Smith points out:

Pettis assumes that because America runs a big trade deficit, tariffs would pump up U.S. manufacturing so much that not only U.S. GDP, but also U.S. consumption, would end up increasing… Trump’s tariffs in his first term didn’t do anything of the kind. Industrial production actually declined after Trump put up his tariffs…

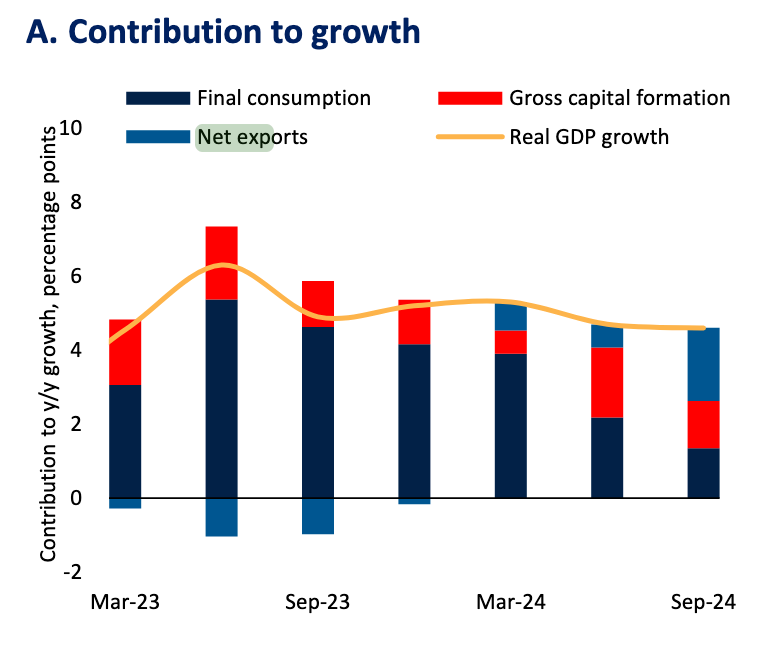

China’s companies responded to slowing domestic demand last year by flooding the world with their products, which has helped prop up declining domestic growth with growth in net exports.

They’re being helped by a weak Chinese yuan, which has joined the slide in global currencies amid a surge in the U.S. dollar. China’s central bank has been trying to nudge interest rates higher to stem its decline, partly to ward off trade frictions with Washington and its other trading partners, but also to discourage capital outflows. But its efforts to mop up cash in the financial system come at a time of year when Chinese are already streaming to ATMs to withdraw cash ahead of the Lunar New Year celebrations. The result has been a cash crunch that’s making life more difficult for China’s banks, with the overnight repurchase rate soaring to its highest since October 2023.

China’s export surge turns out to be largely not to the U.S. and Europe, but to the “Global South”—as Chinese companies build big infrastructure projects in places like Indonesia. While Mexico has displaced China as the largest exporter to the U.S., China’s exports to the U.S. now represents just 15% of its overall exports, down from 20% in 2018. That means higher tariffs in Trump 2.0 will likely exert a lot less pain on China than they did when he imposed them in Trump 1.0.

But China’s surging exports and record trade surplus obviously can’t offset slumping domestic demand and falling producer prices. This has global implications given that China has become one of the world’s largest consumers of commodities, a powerful trend the Financial Times explores in depth:

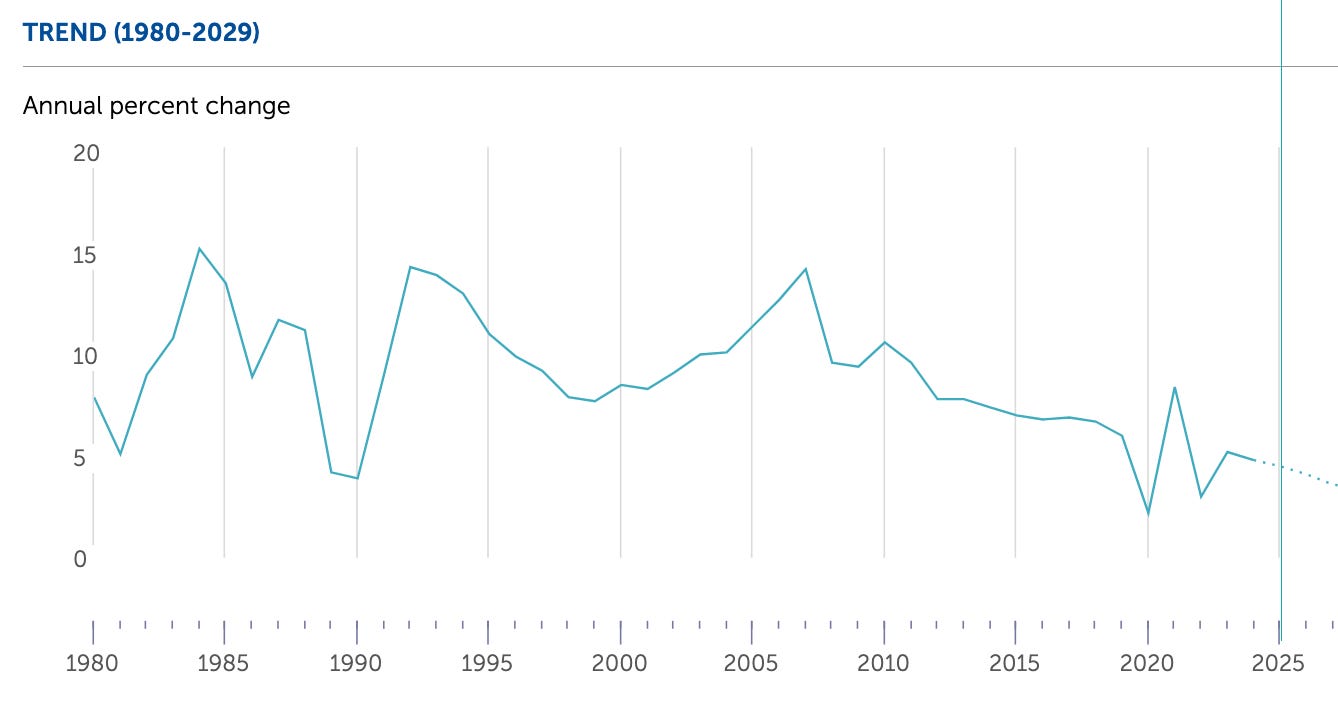

As China built up its cities, according to government data, the country consumed twice as much of the metal in the two decades from 2000 to 2020 as the US did during the entire 20th century. But that supercycle, which started to wane during the Covid-19 pandemic, has now finally come to an end. Last year China’s steel production fell to a four-year low, and is expected to shrink again this year. The country’s consumption of iron ore, a key ingredient for making steel and iron, declined last year after peaking in 2023, according to Macquarie. There are even some indications that Chinese demand for oil is starting to peak—well before most forecasts said it would.

China’s demand may recover somewhat, though, as it now races to replace its carbon-intense economy with greener technology—and develop the computing speed and size that drives artificial intelligence. But this time around, China isn’t running the race alone: the rest of the world, and notably the U.S., are also galloping to build the smart grids, renewable energy plants, and giant data centers they need.They are all competing for scarce resources and trying to develop supply chains that exclude their rivals.