Investors go all in on Goldilocks scenario of AI and Fed rate cuts

(Originally published Sept. 15 in “What in the World“) Investors are putting their eggs in one basket—again.

The ructions of April may be long forgotten, but the U.S. stock market remains just as (maybe even more) dominated by Big Tech as it was when investors were fleeing it. With benchmark indexes setting new records almost daily, analysts again worry that any upset to investors’ blind faith in the promise of AI could drag the entire market down—fast.

According to The Wall Street Journal, the five largest stocks in terms of market capitalization make up 27.7% of the S&P500, up from 11.7% ten years ago. The top five varies slightly depending on who’s up and who’s up more, but the list hews to a group of companies that are to various degrees deeply invested in AI as a profit engine: Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, Broadcom, Meta, Microsoft, and Nvidia.

And AI, or at least its chatbot manifestations, remains a sort of glass-half-empty, glass-half-full product. While its ability to almost instantly craft authoritative answers to even complex questions, mimic convincing language and even render life-like images remains astounding, its accuracy—and its ability to disguise its frequent inaccuracies in convincing language—remains a troubling issue. Given how many successful humans rely on precisely the same ability (a.k.a. bullsh*tting), it remains to be seen whether this ultimately proves a defect or a feature. Yet doubts remain about whether AI is everything it’s been cracked up to be.

Investors are also roughly 80% certain that the U.S. Federal Reserve is going to cut interest rates three times before the end of the year—the first on Wednesday—to help stimulate a weakening job market and thus make life a bit easier for companies trying to make good on this AI gospel. Yet two of the 12 seats on its rate-setting committee, remain uncertain: Trump’s top economic adviser Stephen Miran, whom Trump appointed to replace Fed Board governor Adriana Kugler, could win Senate confirmation later today. And the White House has asked a federal appeals court to remove Fed governor Lisa Cook before her lawsuit against Trump’s dismissal is heard.

With so much riding on so much confidence, the one thing that seems almost certain is disappointment.

One potentially flapping butterfly is a sharp reduction in liquidity in markets for cash, after investors snapped up a big sale of short-term U.S. Treasury debt. When Congress in July raised the U.S. debt ceiling, the Treasury went on a bit of a borrowing spree apparently. The crunch could come today, the deadline for corporate taxes, when the need for cash rises sharply.

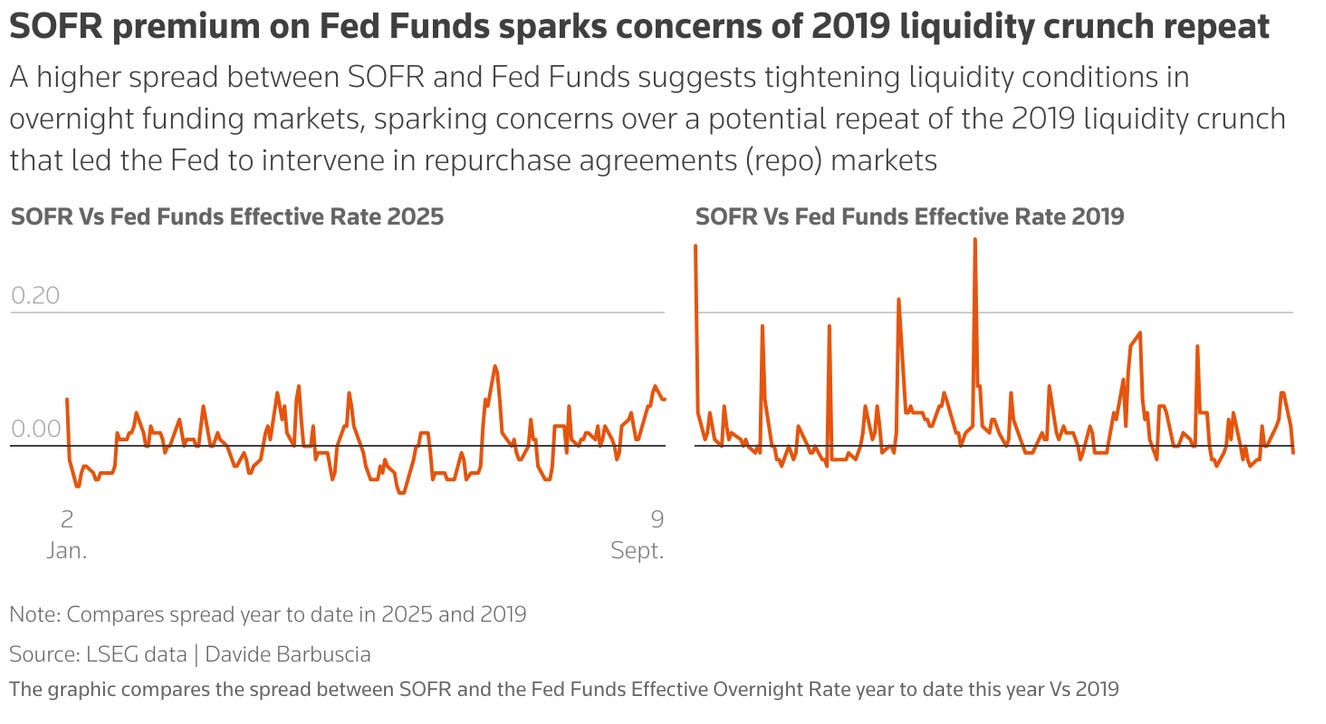

Already, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR), the cost of overnight borrowing using Treasuries as collateral, rose on Friday to 4.42%, the highest in two months. The spread between one-month SOFR forwards and the effective fed funds rate, which is what banks charge to lend cash to each other, rose Thursday to a record 7.5 basis points. That suggests that traders believe the SOFR will be .075 percentage points higher than fed funds rate by end-September, suggesting tighter funding conditions.

Source: Reuters

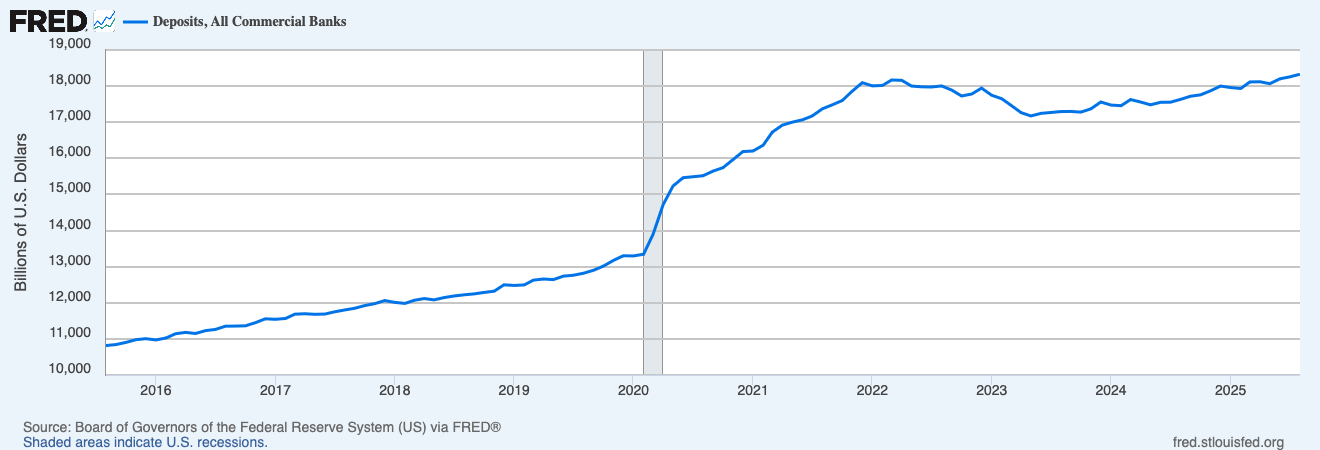

That has given rise to worries that there is a chance, albeit a small one, that markets could undergo the kind of liquidity crunch they did in September of 2019, when the Fed had to inject emergency cash into the economy. Since then, the Fed has created a Standing Repo Facility (SRF) that banks can tap for emergency cash on top of the Fed’s normal purchases of repurchase agreements (in which the Fed buys a security from a bank along with the agreement to buy it back after a certain period of time at a higher price, i.e. a rate of interest—essentially lending the banks money and injecting cash into the financial system). And banks have more cash stashed in deposits at the Fed now than they did back then.

As a result, lending to the Fed by banks through its reverse repurchase facility (in which the Fed sells banks a security along with the agreement to buy it back after a certain period of time at a higher price, i.e. a rate of interest—which the Fed uses to drain cash from the financial system to prop up interest rates) has dropped to $29 billion from $2.6 trillion at the end of 2022.