Beijing denied being tipped off about Moscow’s Ukraine invasion, but it started hoarding grain just months ahead.

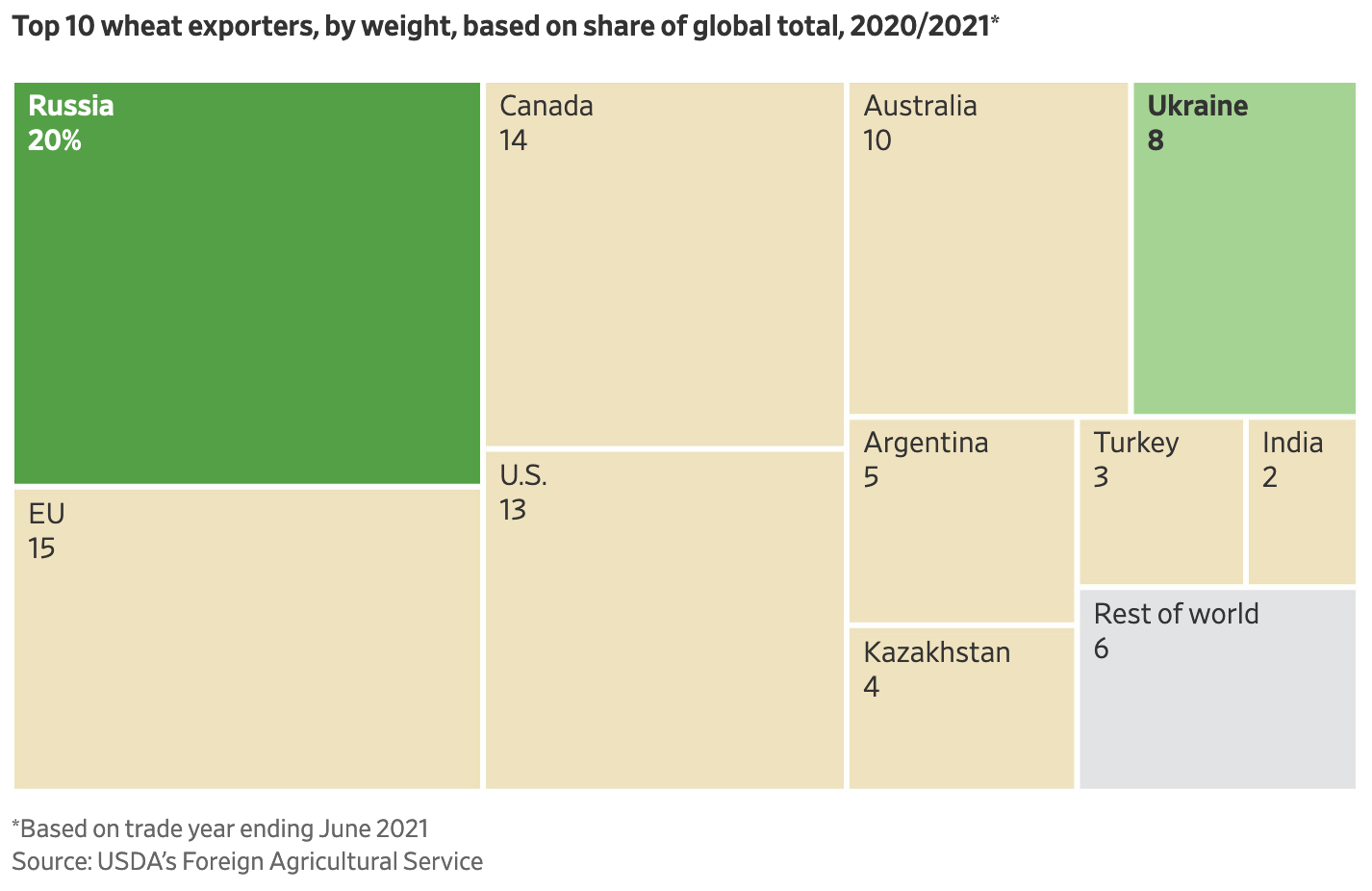

(Originally published May 4 in “What in the World‘) The global grain industry is scrambling to offset the loss of wheat from Ukraine and Russia, which together account for 28% of global wheat exports by weight. Rising prices and fears of shortages of wheat, cooking oil and fuel have sparked panic buying across the Middle East, with importers there shifting purchases sharply to Brazil.

One nation many predicted would be at the forefront of the scramble to replace Ukraine’s lost food exports is China. China is after all among the countries most reliant on Ukrainian supplies. But China began stockpiling grain and other key agricultural commodities only months before the Ukraine invasion as part of a broader plan to reduce its vulnerability to raw material imports amid concerns about climate change, severe weather, pandemic-related disruptions to global supply chains and growing tensions with the West.

China’s political tides have been largely correlated to food supplies, and famine tends to coincide historically in China with violent regime change. That may explain the urgency behind China’s President Xi Jinping’s push in December to bolster Beijing’s granaries. “Considering the persistently rising grain demand, and the complicated international situation, grain security must be highlighted constantly,” he told the annual Central Rural Work Conference. “We’d rather produce and stockpile more. The pressure of more is incomparable to that of less.”

By March rising commodity prices had intensified Beijing’s push for greater self-sufficiency in food. “Who will feed China? China needs to be self-reliant and support itself,” China’s President Xi Jinping told lawmakers gathered that month in Beijing.

China’s stockpiling has become so aggressive, however, that some critics accused it of exacerbating global food-price inflation. The U.S. Dept. of Agriculture projected in January that, by the middle of this year, China will have cornered just over half of the world’s wheat, 60% of its rice and 69% of the world’s corn.

The propitious timing of China’s food-security drive also stands to feed the conspiracy theory that China had prior knowledge of Russia’s plans to invade Ukraine. This despite the fact that it was obvious to anyone by January—including this newsletter—that an invasion was not only imminent, but inevitable. Beijing’s moves could be nothing more than a sagacious recognition that the West was destined for conflict with Russia as it pushed the ranks of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization eastward. Combined with its acute sense of history, including that of Imperial Japan, Beijing may have also seen that as China’s economic growth pushes it to invest in raw material supplies and export markets abroad and the military muscle to secure them, that it would be headed towards inevitable conflict with the United States.

Beijing even began setting aside more arable land for cultivation of soybeans, a crop it had largely surrendered as uneconomical in favor of imports after joining the World Trade Organization in 2002. Sowing soy probably won’t be enough to offset record-high global prices for cooking oil and animal feed as Ukraine’s exports of sunflower oil dry up.

But it could be a sign that we face a long conflict ahead.