As equities binge on AI fantasies, bond investors brace for economic gloom

(Originally published Sept. 12 in “What in the World“) Analysts warn that the bond market doesn’t seem to share the stock market’s giddy optimism.

MarketWatch quotes the head of BNY’s markets macro strategy Robert Savage as saying that, while equity markets appear to view Fed rate cuts as positive for earnings, the bond market views rate cuts as the outcome of a weakening economy. “Who is going to be wrong?” he asks.

What worries analysts like Savage is the apparent disconnect between 10-year yields, which have been falling as the price of bonds rises, and stocks, which keep scaling new records almost daily. The S&P500 has now climbed 18% since April, when investors were freaking out over Trump’s tariff policies. Yields on 10-year U.S. Treasuries have fallen 147 basis points, to just over 4%.

Of course, stocks and bonds can move in the same direction—like when investors believe that the economy is going to accelerate (and, with it, earnings) while inflation will remain low. But this Goldilocks scenario isn’t apparently what’s driving things right now. Bond markets believe the economy is softening, which is what’s driving the Fed to cut rates. And that’s bad news for earnings.

Odds are that equity markets are wrong—or at least will be right for a shorter amount of time. There’s an old adage on trading desks (mostly bond trading desks) that equity investors are idiots and that most of the smart(er) money is in fixed income. Many also worry that equity markets aren’t chasing economic prospects as much as they are dazzled by the promise of AI, whose biggest proponents now dominate the market: Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple, and Google.

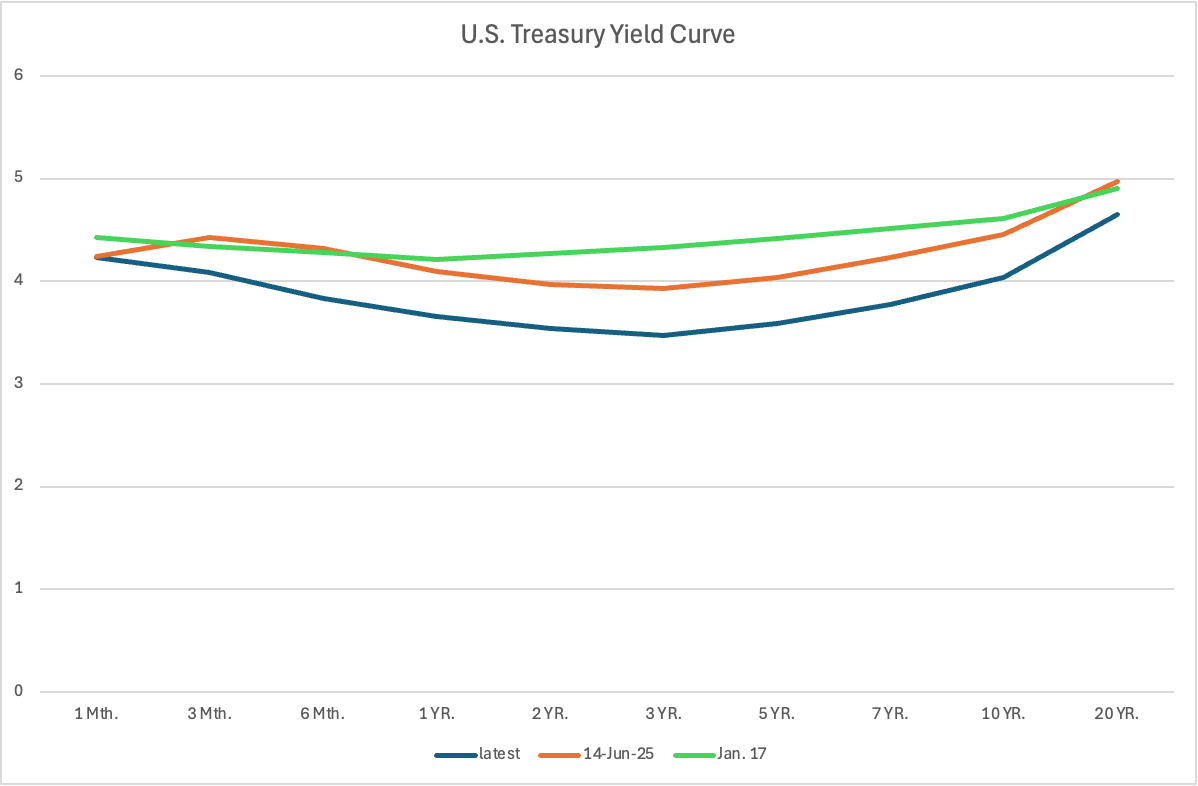

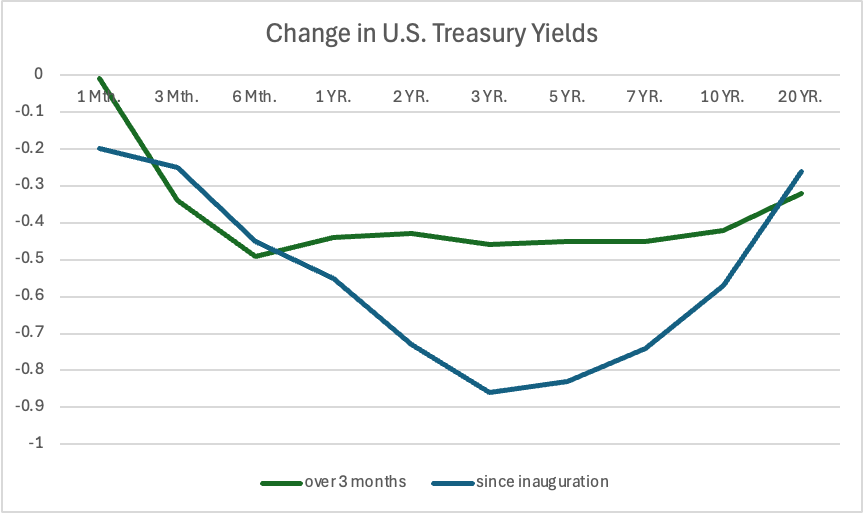

The yield curve for U.S. Treasuries does seem to suggest, though, that much of the action in bonds is a simple scramble for yield in anticipation of lower interest rates. Yields over the past three months have been easing fairly evenly across the curve, with one exception: yields for 6-month T-bills have fallen farthest, fastest.

This inversion in yields is a classic indicator for recession. The problem in this instance is that the yield curve has been inverted at the short end since Trump took office—a vote of no-confidence, if you will.

The yield curve has sagged even further since. The biggest bulge remains in the 3-year tenor, but the most dramatic decline in 6-month yields perhaps suggests that the biggest change is the bond market’s appraisal not of economic prospects, but that inflation has capitulated, and the Fed is now likely to start cutting rates.

Will this trend hold? Perhaps. Markets seemed undaunted by the release by the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ latest consumer inflation data, which showed that prices in August rose by the most in seven months: CPI climbed 0.4%, its largest increase since January. That would normally suggest that the Fed will remain stuck waiting for inflation to ease even as unemployment rises—a recipe for stagflation. But investors are still betting on three rate cuts of 25 basis points each this year.

With U.S. rates now falling even as other central banks reach the end of their rate-cut cycles, pressure could mount further on the U.S. dollar as the lure of higher dollar rates diminishes.