Trump’s policies are toxic, but US Treasury bonds may be too big to fail

(Originally publihsed April 14 in “What in the World“) Reports of the death of the U.S. government bond market may have been greatly exaggerated.

The media has latched wholeheartedly onto a week-long rout in U.S. Treasuries, seizing on the opportunity to label it a measure of just how severely U.S. President Donald Trump is sabotaging U.S. economic and financial strength and undermining faith at home and abroad in the stability and even durability of the U.S. government as a borrower and the United States as a democracy. Even USAToday is now subjecting its readers to bond-market coverage.

The concern is justified. Trump is a threat to democracy, to U.S. government creditworthiness, to the U.S. and global economies, and to the dollar’s dominance in a global system of finance and trade that he has also set alight with his bewildering, on-again, off-again shell-game of miscalculated, misguided tariffs. Worse, his actions have touched off a trade war with America’s fourth-largest trading partner that promises to exacerbate his domestic impact. In its latest response, China has blocked exports of minerals and magnets vital to the global manufacture of cars, planes, semiconductors, and weapons.

Trump is, thus, a threat to the value of stocks and bonds as companies, lenders, central banks, and governments struggle to manage the ever-shifting policy environment he has created. On Sunday, hedge fund billionaire Ray Dalio added his voice to the chorus of plutocrat’s speaking out on the dangers Trump’s policies pose to the economy.

So, the general thrust of bond-market coverage is correct: demand for U.S. government bonds is falling because of concerns about the ability of Washington to service and repay its debt. Trump’s policies appear likely to worsen the U.S. federal deficit and government debt, despite his promises to lower both. Likewise, the U.S. dollar has fallen to three-year lows as investors and central banks scramble for alternatives that are less susceptible to the whims of the U.S. president, including such perennial “safe havens” as gold and the Swiss franc. That’s triggered outflows from U.S. bond funds: investors pulled $15.64 billion from U.S. bond funds in the week after “Liberation Day,” the highest weekly outflow since December of 2022.

Trump’s tariffs also shake one of the biggest sources of demand for Treasuries. One of most stable sources of demand for U.S. government debt comes from the central banks of nations with which the U.S. runs persistent trade deficits, i.e. Japan and China. To keep their currencies from rising with their trade surpluses, both countries’ central banks hold on to the mountains of dollars their exporters bring home and use them to buy Treasuries. If they earn fewer export dollars because Trump’s tariffs make them too expensive, China and Japan will earn fewer dollars with which to buy Treasuries. And they and other investors may even sell Treasuries in advance of lower trade to lock in whatever gains they might now have on their existing holdings.

Indeed, the sell-off in Treasuries is part of a “sell everything” trade that Trump triggered with his April 2 “Liberation Day” announcement of across-the-board reciprocal tariffs. In addition to simply undermining the case for holding dollar-denominated assets, Trump triggered such a dramatic decline in stock prices that he sparked margin calls on leveraged investments, forcing investors to liquidate a range of investments to cover them—everything from high-risk investments like leveraged loan funds and ETFs, to safe-haven hedges such as copper, cryptocurrencies, the dollar, gold, oil, and U.S. Treasuries.

The sell-off in Treasuries has been accelerated by a rapid unwinding of related derivatives trades. As explored in this space last week, the U.S. Treasury market has become highly leveraged as funds borrow money to make bets on Treasuries and Treasury futures. And hedge funds have been selling those bets, then buying the underlying Treasuries to collect an ostensibly risk-free spread only to compound their risk by using the same Treasuries as collateral to borrow more money to buy more Treasuries and sell more Treasury derivatives contracts, and so on.

So, when the price of Treasuries fell rapidly, these hedge funds faced margin calls from their own creditors, forcing them to quickly liquidate some of their estimated $800 billion in Treasuries, accelerating the decline. This is a troubling development, in that it suggests the derivatives market for Treasuries, like the one for U.S. mortgages before the global financial crisis, may have grown so large that it poses a threat to the market for underlying Treasuries—the bonds themselves.

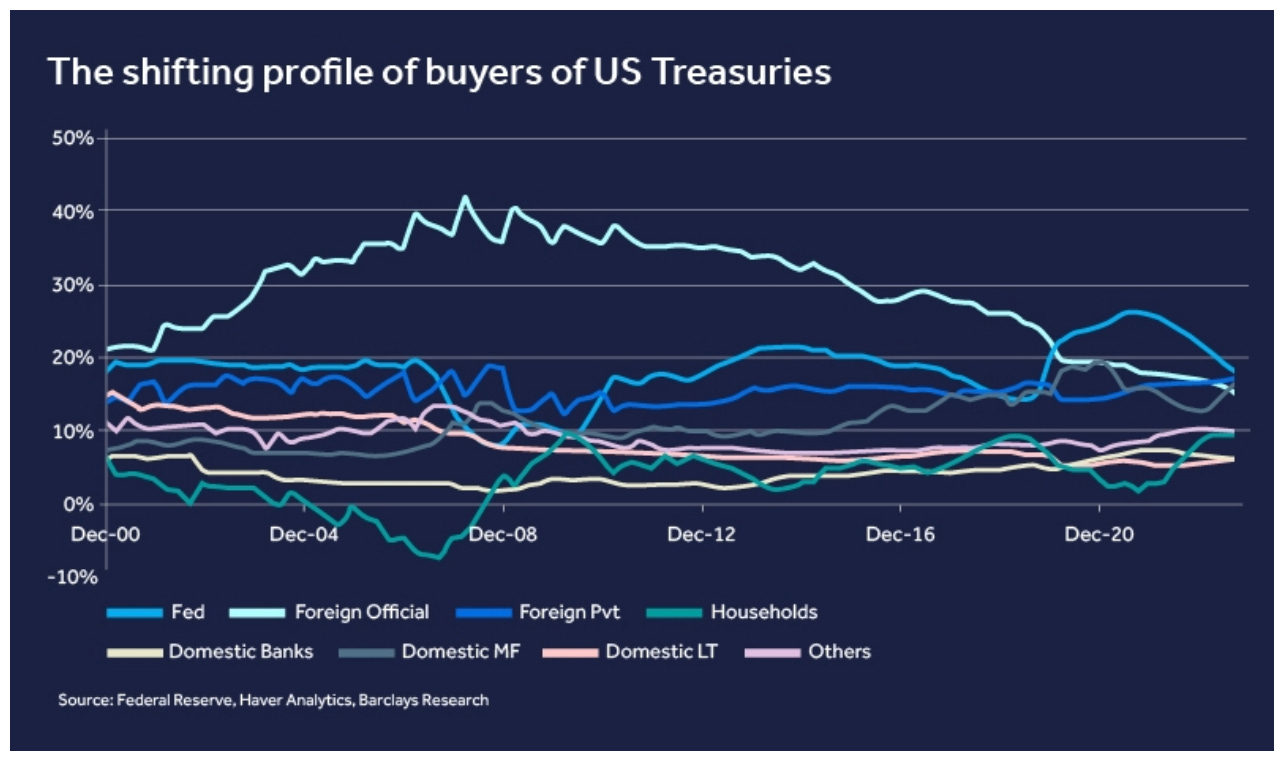

Another reason the bond market has become more susceptible to these kind of movements, as Barclays explains in a new report, is that the buyers are more short-term in focus. The central banks that once provided such a stable source of demand have been scaling back their new purchases for most of the last decade as their reserves stabilize.

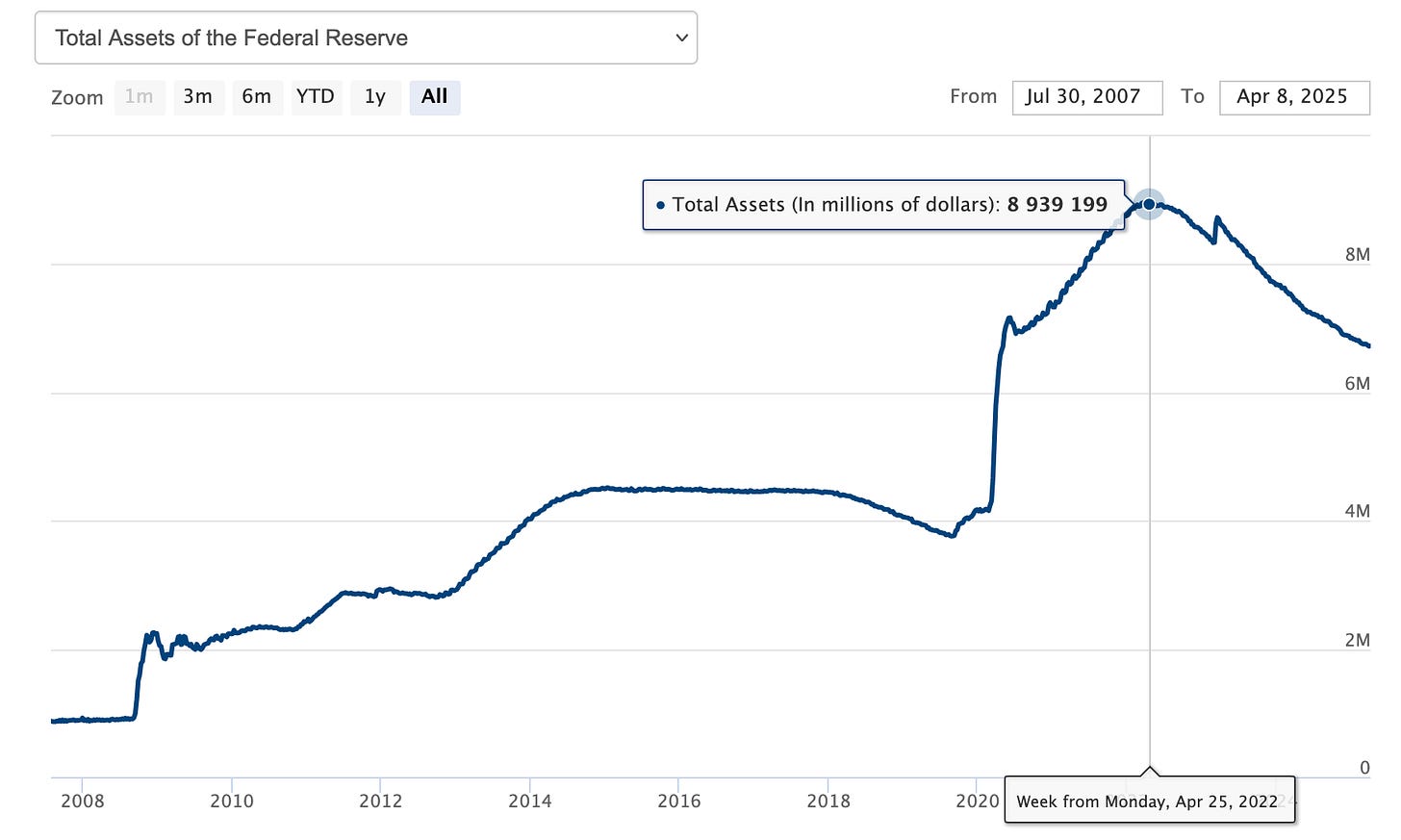

And the Federal Reserve, which gobbled up Treasuries with freshly minted money when it was trying to rescue the U.S. economy with quantitative easing, has been unloading those bonds since the pandemic’s end in 2022, placing steady downward pressure on prices.

As a result, mutual funds and hedge funds make up a greater proportion of Treasury buyers, many of which are using borrowed cash to buy them and tend to hold them for shorter periods. The result, says Barclays, is greater volatility in the bond market, which will now more often resemble the stock market.

There’s a lot of reasons to welcome alarmist coverage of the bond market. Since his advisers appear to have convinced him to ignore his once-favorite policy barometer—stock prices—only the bond market appears capable of getting Trump’s attention. And if the selling gets too intense and the Treasury market does freeze up, it would likely prompt the Fed to step in with liquidity, something that would likely boost markets.

But the weird thing about Treasuries is that demand for them isn’t based entirely on their safety or the creditworthiness of the U.S. government. That’s been ebbing for years. Thanks to soaring debt and perennial threats by Congress to shut down the government, S&P first dropped Washington’s AAA credit rating way back in 2011, with Fitch following in 2023. Only Moody’s still maintains its top, AAA rating on U.S. government debt.

Despite this, the cost of insuring against default by the U.S. government remains relatively stable. After spiking in 2023, credit default swaps on U.S. 5-year Treasuries remain somewhere around 40 basis points, lower than China’s 75bps, but higher than Germany’s 15bps.

On the contrary, one of the biggest attractions of the market for U.S. debt is its sheer size—more than $30 trillion of securities. That volume of bonds provides an unrivaled level of liquidity for investors looking to park cash in something that bears interest that also has a relatively low risk of default. If you need to sell a Treasury quick, there are almost always buyers.

There are some worrisome signs here, too, though. JPMorgan analysts warned last week that large trades were moving yields more than usual, suggesting its depth and liquidity were starting to suffer.

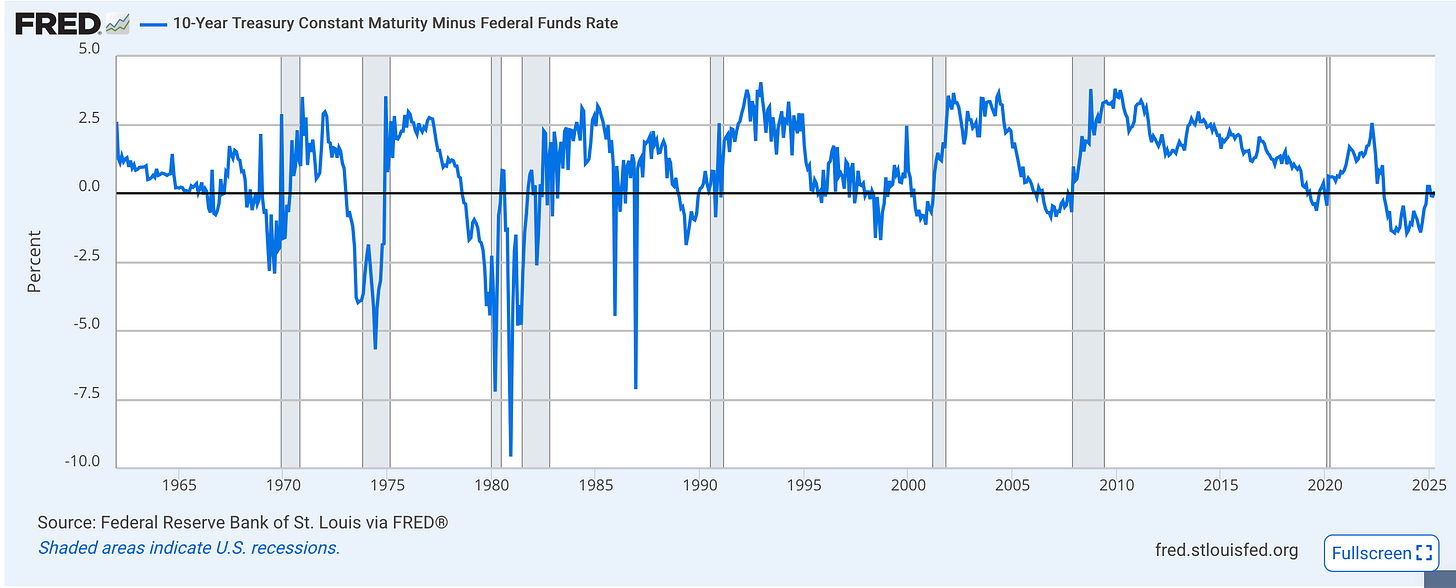

The latest moves in 10-year Treasuries aren’t as dramatic as they might seem, though, when looked at from a broader perspective of the overall Treasury market. For starters, there’s the yield on the 10-year Treasury. It’s leapt from just under 4% on April 4 to nearly 4.5%. That’s dramatic until you step back and realize that it stood at 4.8% in mid-January and had been falling since Trump took office as investors bet that Trump’s policies were so bad they would force the Fed to cut interest rates despite persistent inflation. Trump’s tariffs are much higher than anyone imagined, however, so inflation is likely to be higher, too. That prompted a reversal.

That 10-year yield would mean nothing if the Fed were, in fact, cutting rates. But it isn’t. Thus, the 10-year yield isn’t spiking relative to benchmark interest rates. If and when it does, that’s a major cause for concern.

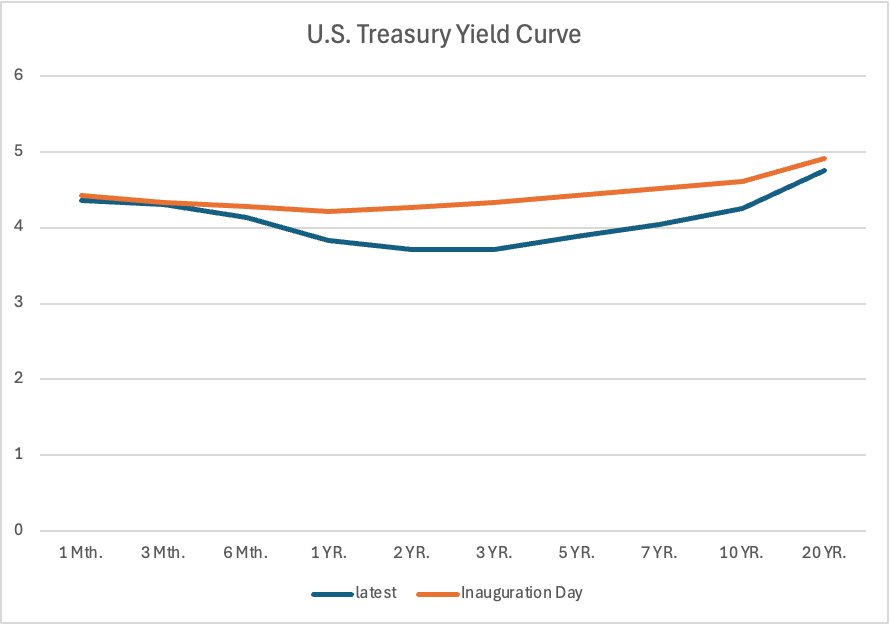

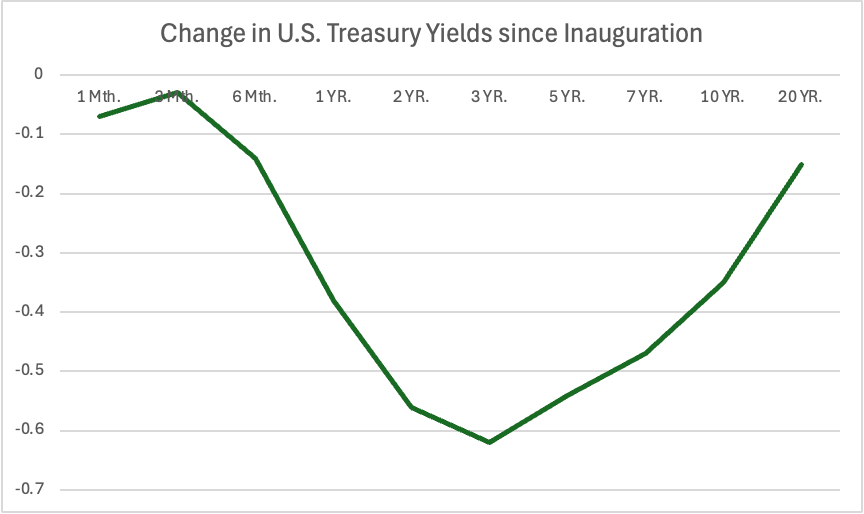

Also, the media tends to focus only on the 10-year Treasury, ignoring the many other maturities in the market. Washington borrows money across a wide range of tenors, from one month to 30 years. So, because investors are increasingly worried about the risks of lending Washington money, they’re tending to favor shorter-term U.S. debt than the 10-year bond.

This flight to safety is evident the U.S. government bond yield curve. Long-term, 7- to 10- year rates have been falling, which Trump and his Treasury Secretary have wanted, but short-term rates are falling even faster, resulting in an inverted curve in the 1- to 3-year portion of the curve. Just two weeks ago, investors were favoring the 3- to 5-year portion of the curve. Moves in this direction often coincide with expectations of recession.

As a result, yields on 3-year and 5-year Treasuries have also surged, but not by as much as that on the 10-year.

At the other end of the curve, yields on 30-year Treasuries, more popular among the longest-term bondholders, have also not climbed as dramatically. That suggests much of the drama in 10-year bonds may be about its overuse as the underlying security in all those derivatives contracts. And while some are wringing their hands over the rise in 30-year yields over the past week, 30-year yields haven’t yet climbed as high as they were as recently as last October.

Make no mistake: Trump’s policies are disastrous and seem increasingly likely to push the U.S., if not the global economy, into recession. The risks remain high for stocks and any high-risk, leveraged assets, including low-rated corporate bonds or leveraged loans and ETFs, or complex derivatives with low liquidity. Ultimately, however, the U.S. Treasury market is insulated to some extent by the fact that there really aren’t any viable alternatives in fixed income. The next-largest market for national government debt, or sovereign debt, is Europe’s at about $15 trillion. Add Japan’s $9.2 trillion and China’s $4.8 trillion and you’re still shy of the market for U.S. Treasury debt.

Washington’s addiction to debt—and investors’ need to feed that addiction—may paradoxically be one of its greatest strengths.