Trump’s destruction of US-led economic order revives risks in Treasury bonds

(Originally published April 9 in “What in the World“) Stocks slid again as Trump escalated his trade war.

The S&P500 fell another 1.6% Tuesday to its lowest in almost a year. It has dropped 12% in the past week since Trump announced his “reciprocal” tariffs and has fallen almost 17% since his inauguration.

Trump said his new, 50% retaliatory tariff against China would take effect today if China doesn’t withdraw its own, 34% retaliatory tariff against his own. China’s Commerce Ministry vowed to “fight to the end.” Trump’s latest tariff brings to 104% the tariffs on U.S. imports of goods from China—and that’s just those he has imposed since taking office. It doesn’t include tariffs he imposed in his first term that were maintained or even raised by former President Joe Biden. Combined, the average tariff rate on Chinese imports is almost 125%.

The tariffs are already sparking U.S. layoffs: Stellantis, which makes both Chrysler and Jeep vehicles, has laid off 900 workers who supplied engines and parts to factories in Canada and Mexico. Economists also warn that heavy market losses could curtail spending by middle-class and affluent Americans, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy in which stock prices not only reflect the economy’s prospects, but determine them. The U.S. National Federation of Independent Business said its Small Business Optimism Index suffered its biggest monthly decline in March since June 2022.

Trump has told citizens to be patient and trust him, that dismantling the global trade system, tanking the stock portfolios and potentially plunging the U.S. economy into recession are all part of a plan to blow up what he says is a system unfair to the U.S. But the plan has been executed with little preparation and White House officials have all but conceded they have no plan for handling the repercussions they have unleashed on the global economy and financial system.

Trump’s vision seems to rely on a rose-colored vision of America circa 1925, or even 1895, in which Americans toil in factories for labor-intensive manufacturing industries making shoes and fabric. He’s even trying to revive the use of coal and that happiest of occupations, coal mining.

The stock market’s drastic declines have prompted margin calls, which force leveraged investors to sell other assets to cough up cash and collateral. Some of the more obvious victims are leveraged exchange traded funds, which buy assets with borrowed cash that in good times produce outsized returns. In downturns, their losses also multiply: these leveraged ETFs lost $25.7 billion in value late last week.

But margin calls also help explain why the market rout has now spread to other assets until recently considered relatively safe havens, such as copper, cryptocurrencies, the dollar, gold, oil, and U.S. Treasuries, sparking a “sell everything” trade.

There are, naturally, other factors driving these assets: the inherent worthlessness of gold and especially of cryptocurrencies, for example, or conversely copper’s connection to economic growth and the need (or lack thereof) for raw materials. And Trump’s xenophobic policies of economic self-harm are undoubtedly sparking capital flight and thus a weaker dollar, undermining its role as a global reserve currency.

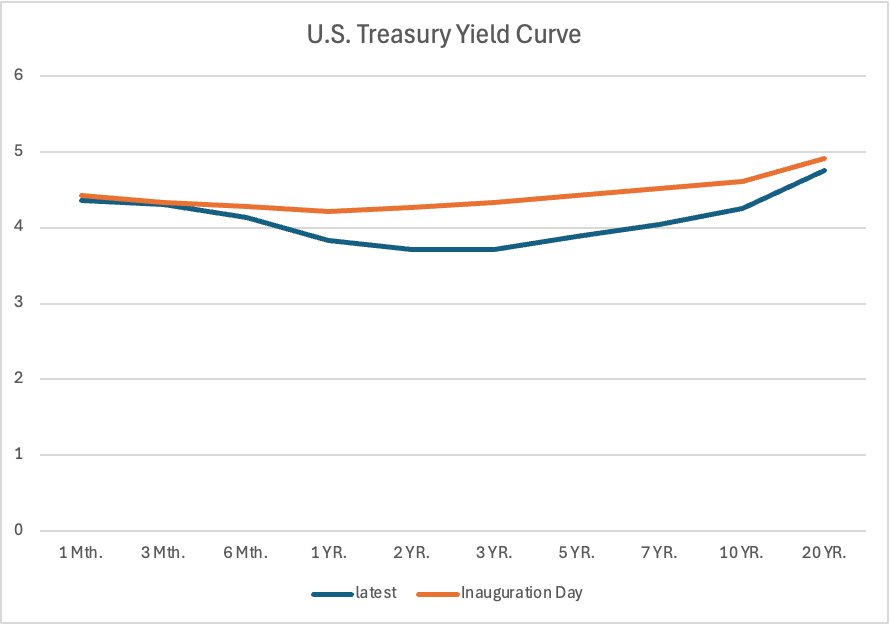

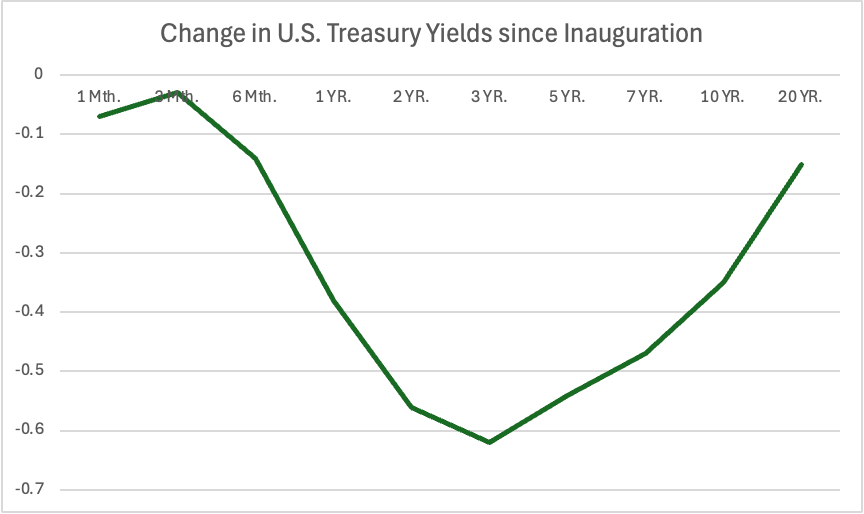

But the factors driving volatility in the U.S. Treasury market are cause for serious concern. Since Trump’s inauguration, the logic driving this market for what has traditionally been considered the safest of assets has vacillated wildly. Investors first sold U.S. government debt in the belief that Trump’s tariffs, tax cuts, and spending would hurt Uncle Sam’s creditworthiness, keep inflation high and thus preventing the Federal Reserve from cutting interest rates. Then, as it became clearer just how much damage Trump was inflicting on the U.S. economy, they started buying bonds in the belief that Trump’s policies would spark such a sharp slowdown in growth that the Fed would have to cut rates.

Now, suddenly, investors are selling bonds again. Part of that is recognition that Trump’s trade war is raising the risks of stagflation and that the Fed may have to stand pat on rates even as growth stalls and government revenues dwindle and hurt its ability to repay its mounting debt. Tariffs also mean lower export earnings for big trade-surplus nations like China and Japan, which typically keep their currencies from shooting up by using their dollars to buy, what else? U.S. Treasuries.

Some clarity comes from looking at bond maturities and the yield curve. Investors aren’t just buying or selling U.S. Treasuries indiscriminately. They’re increasingly favoring the greater certainty of shorter-term U.S. debt. In other words, they want to lend to Washinton, but prefer to be paid back sooner, please. This flight to safety is evident in the bull flattener taking place in the Treasury market. Long-term, 7- to 10- year rates have been falling, which Trump and his Treasury Secretary have wanted, but short-term rates are falling even faster, resulting in an inverted curve in the 1- to 3-year portion of the curve. Just two weeks ago, investors were favoring the 3- to 5-year portion of the curve. Despite the name, a bull flattener usually coincides with expectations of recession.

But such fundamental thinking doesn’t fully explain what’s happening. After all, the market still predicts the Fed will cut rates three, maybe even four, times this year. So why sell bonds? Perhaps because they aren’t nearly as safe as they’ve long been treated.

The Financial Times offers an intriguing, and troubling, explanation for what The Wall Street Journal has struggled to explain. As FT Alphaville describes, the U.S. Treasury market has become incredibly leveraged in much the same way that the U.S. housing market became leveraged before the global financial crisis. Funds have been buying Treasury futures to bet on bond-market movements without having to pony up the cash for actual Treasuries. Typically, such positions are used to hedge cash positions, but with the cash required so low, many simply buy the futures without any corresponding position in actual bonds.

For funds to buy these futures, someone has to sell them. That’s where hedge funds come in. They write the futures contract and sell them. Why? Because, as FT Alphaville write, “Treasury futures contracts typically trade at a premium to the government bond you can deliver to satisfy the derivatives contract.” A premium in price for a bond translates into a discounted yield. So, by selling the derivative and buying the physical bond, a hedge fund can collect a profit from the slight difference between the yield they collect on the real Treasury and the lower yield they have to pay on the futures contract. This is called a basis trade.

So far, so good. The problem is that, to make these tiny basis trades worth their time, hedge funds leverage them by using the actual bonds they buy to cover their futures risk as collateral for repurchase agreements—they sell the bonds with a promise to buy them back later at a slightly higher price. This repo agreement is effectively a loan whose collateral is the underlying bond: if the bond’s seller doesn’t repay, the bond’s buyer gets to keep the bond. By leveraging their cash bonds to borrow money and buy more, the hedge funds can sell even more Treasury futures, and so on. How many times can they repeat this? FT Alphaville estimates up to 100: “just $10 million of capital can support as much as $1 billion of Treasury purchases.”

So how big is this? Hard to say. But FT Alphaville reckons a good proxy is the net short positions hedge funds hold in Treasury futures, which has roughly quadrupled in the past four years, to $800 billion.

The trouble comes when the Treasury market falls or just becomes more volatile. Then, hedge funds have to put up more collateral against their repo agreements. If they can’t, their lenders can seize the Treasuries already posted as collateral and sell them to cover their losses.

Some of this risk is offset by the fact that futures contracts holders also have to post collateral. But you get the point: when the market becomes more volatile, the risk rises that if just one fund manager fails to post collateral on a futures contract, it could force a hedge fund to default on 100 times that amount in repo contracts.

And if all futures contracts start to move rapidly in one direction and all the fund managers start a simultaneous mad dash for collateral, it could create a liquidity crisis that torpedoes the supposedly safe Treasury market. That’s what ostensibly almost happened in March 2020 before the Fed stepped in.

The U.S. is meanwhile telling roughly 900,000 recent asylum seekers in the United States to leave immediately. The Dept. of Homeland Security sent an emailed warning to leave to immigrants who used an app called CBP One.

The app was created during the administration of former President Joe Biden and gave successful applicants the right to cross the U.S.-Mexico border and stay legally in the U.S. for two years while applying for political asylum. After President Donald Trump took office, however, the app has been re-named CBP Home and re-engineered for immigrants to use for “self-deportation.”

Homeland Security has also revoked the visas of more than 500 foreign students studying in the U.S.