As China squares off against Trump, the dollar’s meltdown may be underway

(Originally published April 21 in “What in the World“) As his nation’s currency and its financial markets continue to swoon, Trump has predicated his trade—let’s be kind and call them “policies”—on being able to squeeze a deal out of China.

One problem: China’s President Xi Jinping won’t give Trump the time of day. According to The New York Times, U.S. President Donald Trump is hoping for a high-profile summit in which he can be seen hashing things out with Xi. “I have great respect for President Xi,” Mr. Trump said last week. “He’s been a friend of mine for a long period of time, and I think that we’ll end up working out something that’s very good for both countries.”

But Xi’s no idiot. And he’s undoubtedly heard Trump’s Vice President JD Vance sum up the administration’s attitude toward trade with “Chinese peasants.” So, he knows Trump won’t treat him as an equal and will instead try to demonstrate the kind of dominance he’s done with other world leaders, from his weird handshakes to his tongue-lashing of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky.

Beijing has also undoubtedly read the White House’s manifesto on trade, even if Trump hasn’t. Beijing’s leaders understand that Washington’s goal is to place China under a kind of financial suzerainty. But what Washington seems incapable of remembering (a mental block by no means limited to Trump or to Republicans) is that it’s exactly that kind of suzerain relationship China wants to re-establish with the rest of the world—to re-gain the preeminence it enjoyed before the gunboats and unequal treaties of the mid-19th century.

That’s China’s longer-term ambition. Yet Washington’s continued failure to treat it as a respected equal, instead denigrating its people as “peasants,” only reinforces Beijing’s conclusion that the U.S.—and the West in general—is determined to prevent China from regaining its natural place in the world and even return China to subjugation. Trying to browbeat China for unfair trade practices is, for those with sufficiently long memories, the 19th century teapot calling the 21st century coffee kettle black.

Rather than negotiate China’s surrender with Trump, therefore, Xi has gone on an unlikely diplomatic offensive. Xi spent last week trying to rally support from China’s neighbors in Southeast Asia. His goal? Head off Trump’s efforts to isolate China by offering to reduce his reciprocal tariffs if they promise to block Chinese imports and Chinese manufacturing investment. China has instead vowed to fight to the end. It has already retaliated with tit-for-tat tariffs and prepared to cut U.S. imports of LNG and food. On Monday, it threatened retaliatory measures on any country that cut such a deal with Trump.

As for Trump, he is determined to fight China down to the last American consumer. Having already imposed a 145% tax on Chinese imports, he’s moving ahead with plans to add port taxes on the Chinese-owned ships bringing them in.

Not satisfied with sabotaging his electorate, Trump continues to threaten his central banker for failing to cut rates and worsen the inflationary impact of Trump’s tariffs. Despite reports that Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent had helped talk him out of it, Trump’s economic adviser Kevin Hassett said Friday that Trump was still considering whether he could fire Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell.

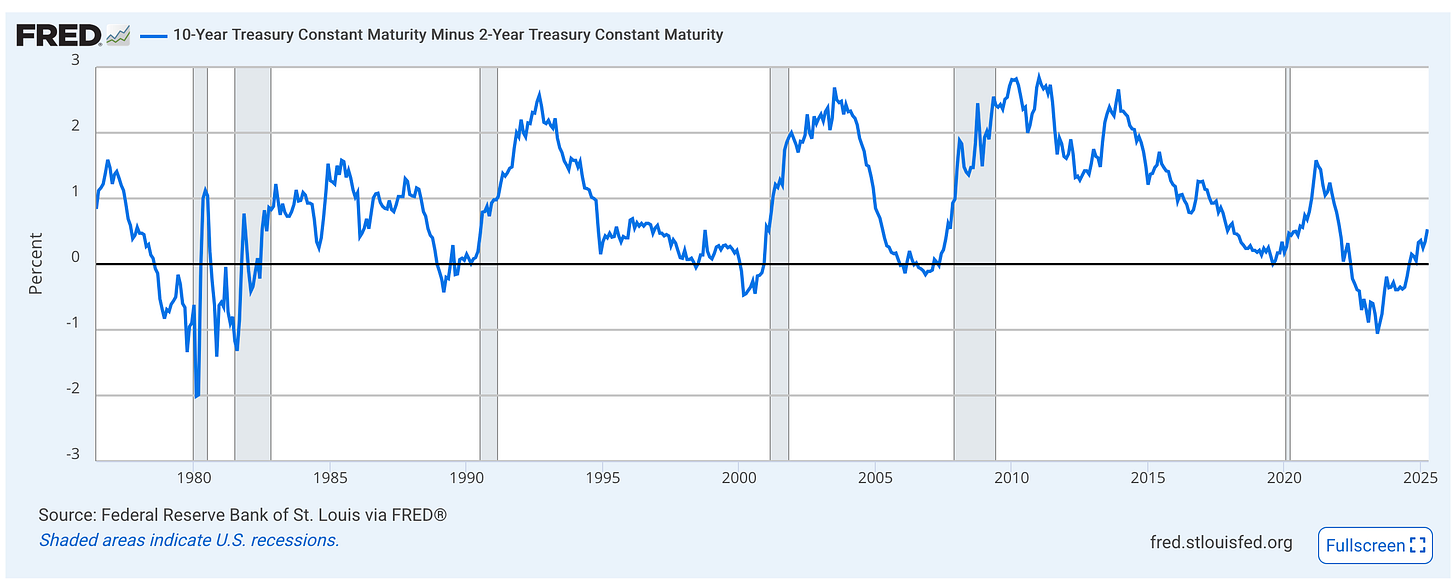

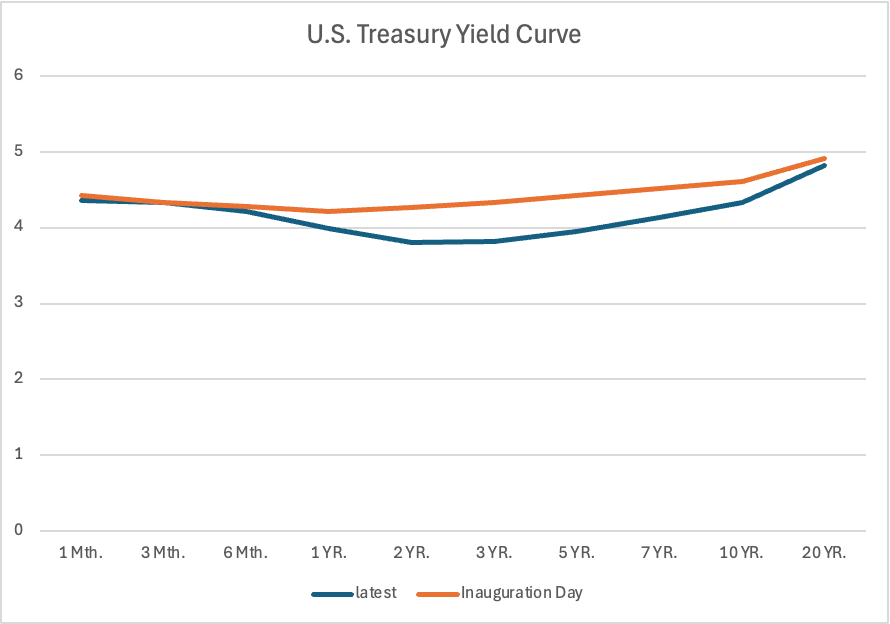

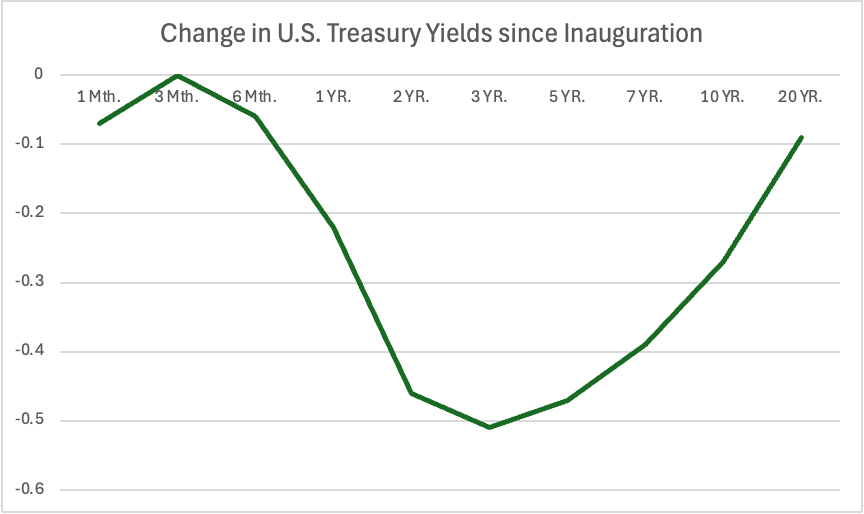

While the turmoil he has wrought in financial markets is nothing to sneeze at, some financial doomsayers are pointing frantically at the steady rise in what bond markets call the “term premium.” That’s the difference between bond yields for shorter maturities and longer-term yields, like between the 10-year and the 2-year. The doomsayers warn that a sharp rise in the term premium is a worrying measure of dismay about how Trump’s policies are hurting faith in U.S. government policy, the U.S. government’s creditworthiness, and thus demand for U.S. government bonds.

And this is by and large true. As discussed in this space earlier, investors worried about Trump’s impact are less eager to lend to the government for 10 years than they are for two to five years. That’s because longer-term loans represent a longer period of risk that the borrower doesn’t repay. That’s the term premium lenders demand for that risk. The higher the term premium, the higher the perceived risk of lending over a longer period. It’s natural that it should be positive.

It wasn’t that long ago that this term premium for U.S. bonds was negative. That’s typically regarded as a harbinger of recession: investors are so uncertain about immediate prospects that they’d rather lend money for longer. So the fact that the U.S. economy didn’t fall into one was considered a real puzzler. When it went positive again, some saw it as a sign that the Fed had managed a soft landing and breathed a sigh of relief.

While negative term premiums have been considered a forward indicator of recession, sharp increases in the term premium have also been considered a lagging recessions indicator. They typically have occurred when the economy was subsequently found to be in recession. Keep in mind that, because it takes two consecutive quarters of negative growth to qualify for a technical recession, you don’t tend to find out you’re officially in a recession until you already know it.

The problem is, we’re not yet seeing the kind of sharp increases in the term premium that we’ve seen in previous recessions.

Trump may be on his way to throwing the U.S. economy into recession, wrecking the stock and bond markets and torpedoing the U.S. dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency. Goldman Sachs warns that Trump has eroded dollar’s “exorbitant privilege” and predicts the greenback will lose favor to the Euro.

But it hasn’t happened yet.