Markets keep Trump from delivering Powell his signature epithet: ‘You’re fired!’

(Originally published July 18 in “What in the World“) Firing Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell could actually push long-term interest rates higher.

Trump has kept markets guessing in recent days about whether he might dismiss his central banker. Markets have been sending him warning signals that he shouldn’t. Replacing Powell might win Trump a lower short-term interest rate. But markets, not the Fed, control long-term interest rates, like the yield on the 10-year Treasury. And it’s that rate that serves as the benchmark for key lending rates like mortgages.

Investors are worried that, with Trump pushing Powell to lower short-term rates, inflation will remain high, while his growth-killing policies sink consumer spending and corporate investment—and with them tax revenue—even as his new budget expands federal debt. That is making stagflation more likely, as Council on Foreign Relations fellow Rebecca Patterson explains, and making lending to the U.S. government money riskier.

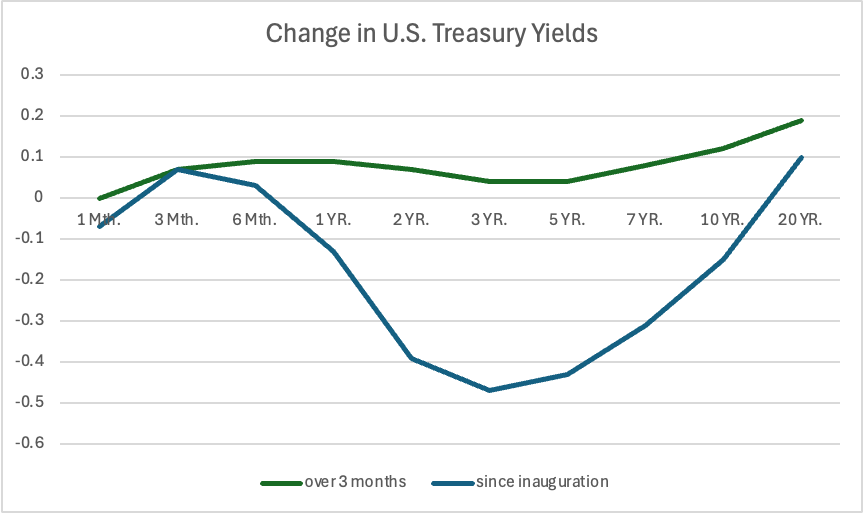

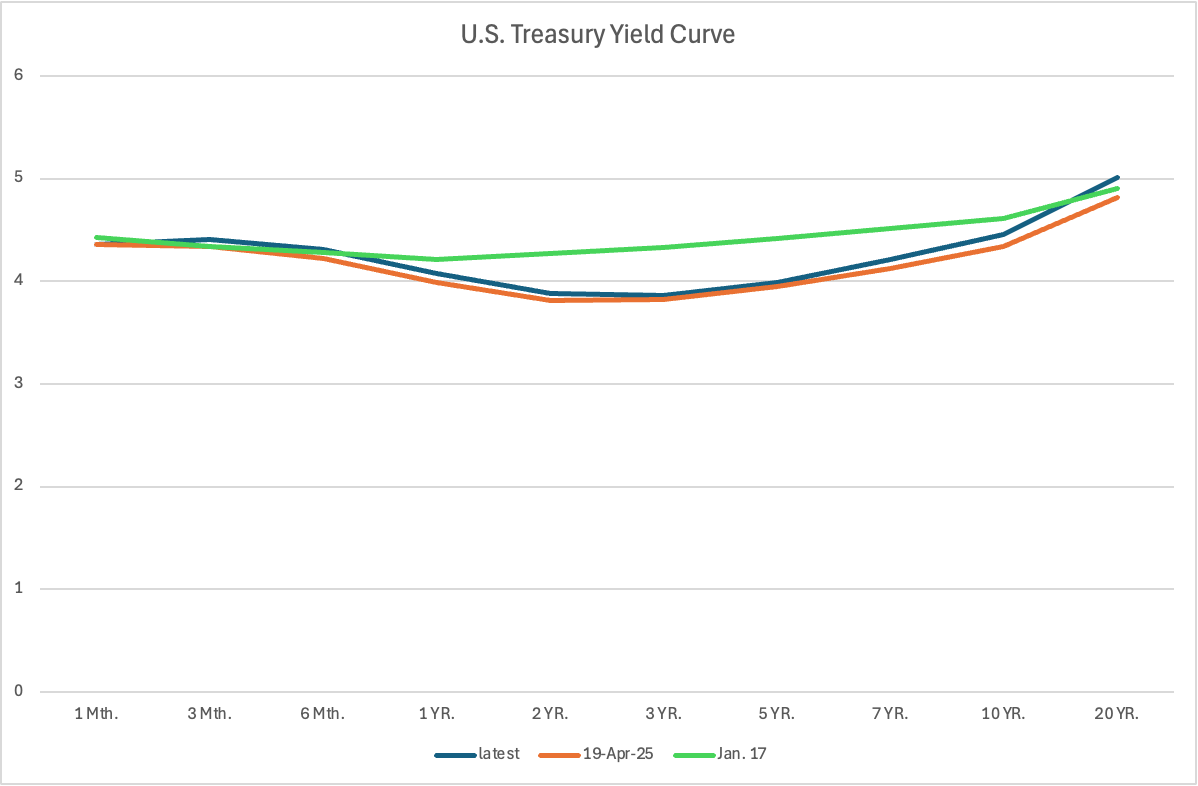

The cost of borrowing for the U.S. government has been rising across the yield curve in the past few months, with yields rising on both short-term, 1-year T-bills, and longer-term, 10-year Treasuries. That’s in stark contrast to the first few months of Trump’s term, when yields were falling and investors stampeded into 3- to 5-year government debt, causing a sharp inversion of the yield curve.

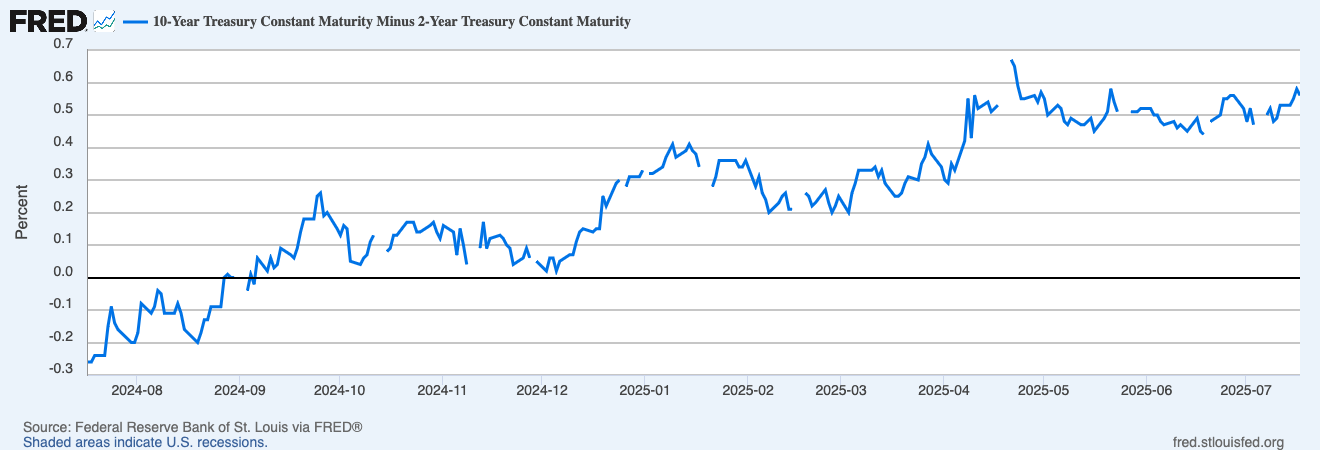

Another new trend is that the gap between what it costs the government to borrow short-term and what it must pay investors for to borrow over a longer period—known as the “term premium”—has plateaued over the past two months, ending its steady climb in Trump’s first few months.

What does this tell us? Your guess is as good as mine, I’m afraid. On the one hand, markets seem to have grown immune to Trump’s bluster and focus more on the modest results of his policies than his more dramatic threats. That’s even given rise to a perverse optimism, a “Trump always chickens out,” or TACO trade.

While Beijing may be shunning U.S. Treasuries, foreigners are buying them again because, at the end of the day, there’s still no government bond market as deep and liquid as the U.S. government bond market. The cost of insuring 5-year U.S. debt against default has fallen sharply since April’s ructions and the U.S. dollar index has recovered some ground from the 3-year lows it touched at the end of June.

While pessimism may not be as acute as it was in April and May, it also seems more pervasive, something that also seems to be reflected in the yield curve. Uncertainty about what crazy thing Trump might do next (like firing Powell) is pushing rates up for short-term bonds with maturities of less than a year, better known as Treasury bills. Worries about the long-term consequences of Trump’s policies on the economy and the federal deficit, meanwhile, are pushing up yields on the long-term 10-year Treasury.

One of the interesting consequences of this new trend is that the inversion in the yield curve that defined the chaos of Trump’s first few months in office has abated somewhat. And after shifting dramatically into 3-year debt, investors seem to be tiptoeing back out the yield curve into 5-year debt. Yields on those tenors have risen in the past three months, but not as much as yields at the short- and long- ends of the curve.