Beijing resorts to Jedi mind tricks to avoid a crisis it can’t afford to fix

(Originally published Aug. 31 in “What in the World“) Rather than deploy taxpayer funds to bail out China’s debt-addled economy, Beijing has apparently decided it can achieve the same results more cheaply using agitprop.

Authorities have launched a counteroffensive against what they call “cognitive warfare” by the West against China’s economic confidence. Western politicians and news outlets, Beijing’s mouthpieces allege, are merely cherry-picking data to make it appear as though China’s economy is in a tailspin. The truth is that things are fine.

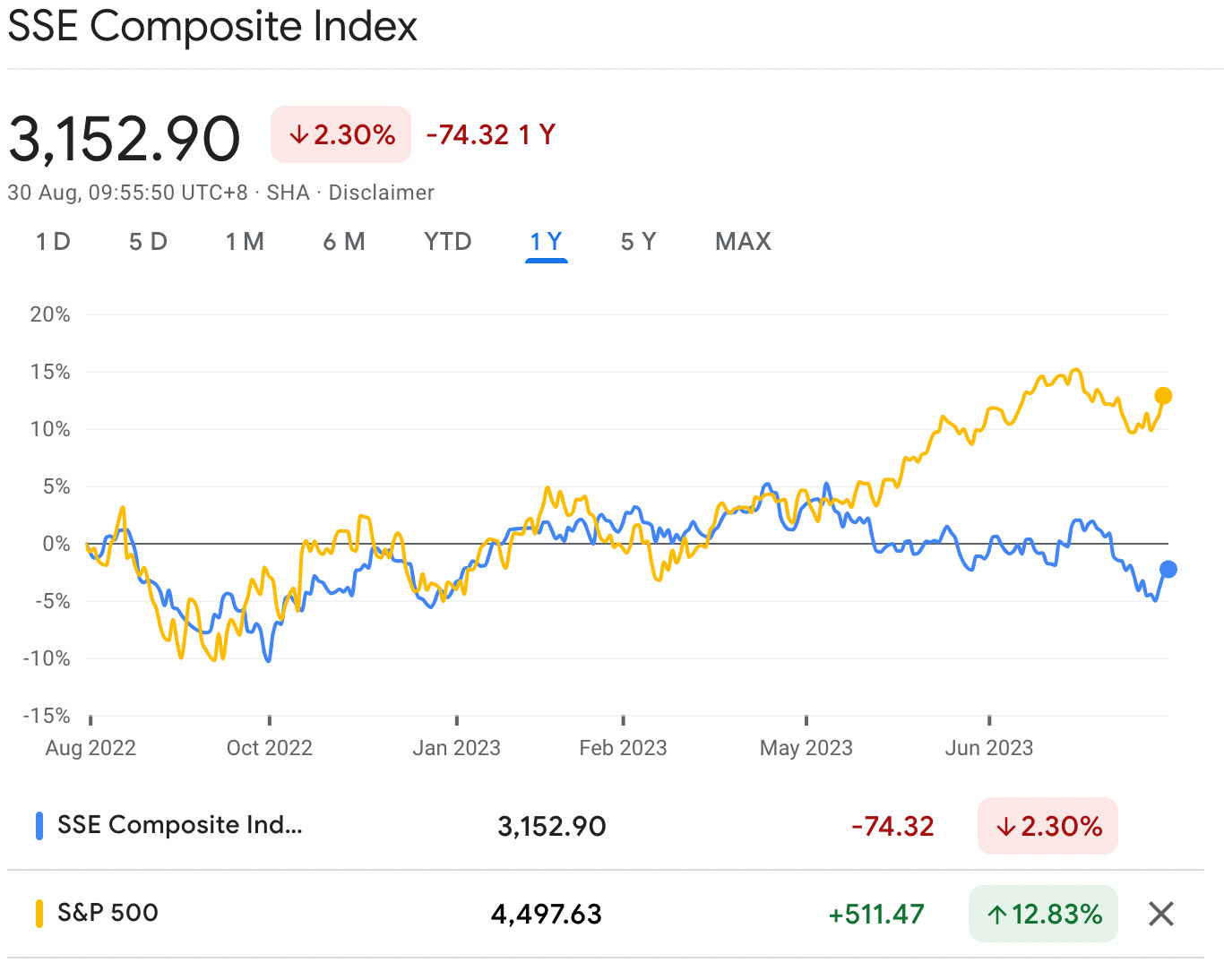

Gaslighting the Chinese public about a downturn they can see and feel may not revive consumer spending. People can see their own bank account statements and the stock market’s benchmark index. As a result, they’re moving money abroad as fast as they can. Fund managers in China have already almost sold out this year’s $165.5 billion quota for qualified domestic institutional investor (QDII) funds, which invest in stock markets outside China.

But depriving consumers and investors of information about major stress points in the credit system can arguably slow the contagion effect they might have. If only your creditor knows you’re bust, no one else will stop lending you money or filling your orders.

It’s that logic that prompted China’s National Bureau of Statistics earlier this month to stop publishing worsening data on youth unemployment. No news is good news.

Regulators and employers have also reportedly been browbeating domestic economists, warning them to avoid saying anything negative about the economy, whether falling prices, skittish consumers or capital flight. And the China Securities and Regulatory Commission has reportedly scolded analysts for badmouthing the economy, too.

Adding to the questions over the veracity of China’s economic data are recent restrictions on access to Wind, the financial and economic database that is China’s equivalent of Bloomberg and recent crackdowns on foreign consultants for alleged espionage. The result: a China “truth” discount. Among investors closely watching China, it’s become given that however poorly Beijing may admit the economy is doing, it’s very likely doing much, much worse.

In April, China passed a revised Counter-Espionage Law, which took effect July 1. While the revised law appears mainly aimed at outlawing cyberattacks, it also stipulated that all “documents, data, materials, and items related to national security and interests” were considered on equal legal footing as official state secrets, without offering a clear definition of what would constitute “national security and interests.”

According to Reuters, the revised law empowers authorities to seize “data, electronic equipment, information on personal property” and to stop people from entering or leaving the country as part of any investigation into violations. Foreign businesses say they now can’t tell what economic data, market research and other financial data in their possession might end up falling afoul of the law. It’s that kind of unpredictability that U.S. Commerce Secretary said during a foot-in-mouth moment on a high-speed train to Shanghai from Beijing that’s making it “uninvestable” to U.S. companies.

But Beijing has long believed it can manipulate the economic narrative by moving the goalposts, or just removing them altogether.

Beijing’s GDP reporting has also tended to raise eyebrows among economists. Even in quarters when it was clear to anyone with eyes that growth was stumbling, the economy’s official performance would come in at or near the official target.

Eventually, economists have come to look at China’s GDP numbers as a carefully crafted narrative, like many on TV, “based on a true story.” They may not be spot on, but they are at least “directionally accurate.” Why not just ignore them, then? “Because there is no authoritative alternative.” And at the end of the day, economists must rely on data from somewhere to do their jobs.

Economists have periodically latched onto alternative indicators as proxies for gauging growth trends, like steel production or power consumption. But whenever authorities in Beijing get wind that such an indicator has gained currency, its reporting gets put into a format that make annual comparisons more difficult to calculate—reporting it based on an index, for example, or expressing monthly data relative to a point at the start of the year. Recently, popular indicators have simply disappeared from the official reporting calendar, raising new questions about whether Beijing was trying to whitewash its economic performance.

Beijing’s efforts to massage the truth don’t stop at its own shores, of course. Meta, the company that runs Facebook, says it just dismantled a huge misinformation campaign launched by Chinese law enforcement in 2019 to push its own narrative and undermine China’s rivals. Meta says it shut down 7,704 Facebook accounts, 954 Facebook pages, 15 Facebook groups and 15 Instagram accounts that were being used as part of the campaign, the seventh it has discovered in the past six years.

Unfortunately, no news is also bad news. And in the increasing void of information, China’s investors are creating a negative feedback loop. Their outflows of capital risk pulling domestic asset prices—including property—even lower, exacerbating the risk of a property market crash, widespread defaults, and a financial crisis.

Analysts and economists have been wringing their hands over Beijing’s reluctance to step in with taxpayer funds to arrest the crisis in a TARP-style bailout.

(In this scenario, Beijing would coordinate the bankruptcy of one or more systemically important developers, shadow banks, commercial banks—a la Bear Stearns and Lehman—thus pushing them to a deeply discounted value and wiping out their shareholders. At the same time, it would coordinate with healthier banks and market makers to keep markets functioning and liquidity moving through daily markets so businesses can continue to function. Then, it would borrow money by selling national bonds to buy these failed institutions, restructure them and later sell them to the private sector for a profit.)

Theories abound, though, about why Beijing hasn’t done this. One is that it already has been, since around 2015, been quietly and gradually trying to prop up the system while bailing it out, only to fail. Another is that President Xi Jinping doesn’t want to use good socialist cash to bail out the banks, developers and wealthy shareholders who got rich from the debt bubble. That’s not only what bankers call a “moral hazard,” in that encourages profligacy, but could be devastatingly bad politics for a president who’s been tackling growing income inequality by cracking down on Big Tech only to help generate a record-high youth unemployment rate.

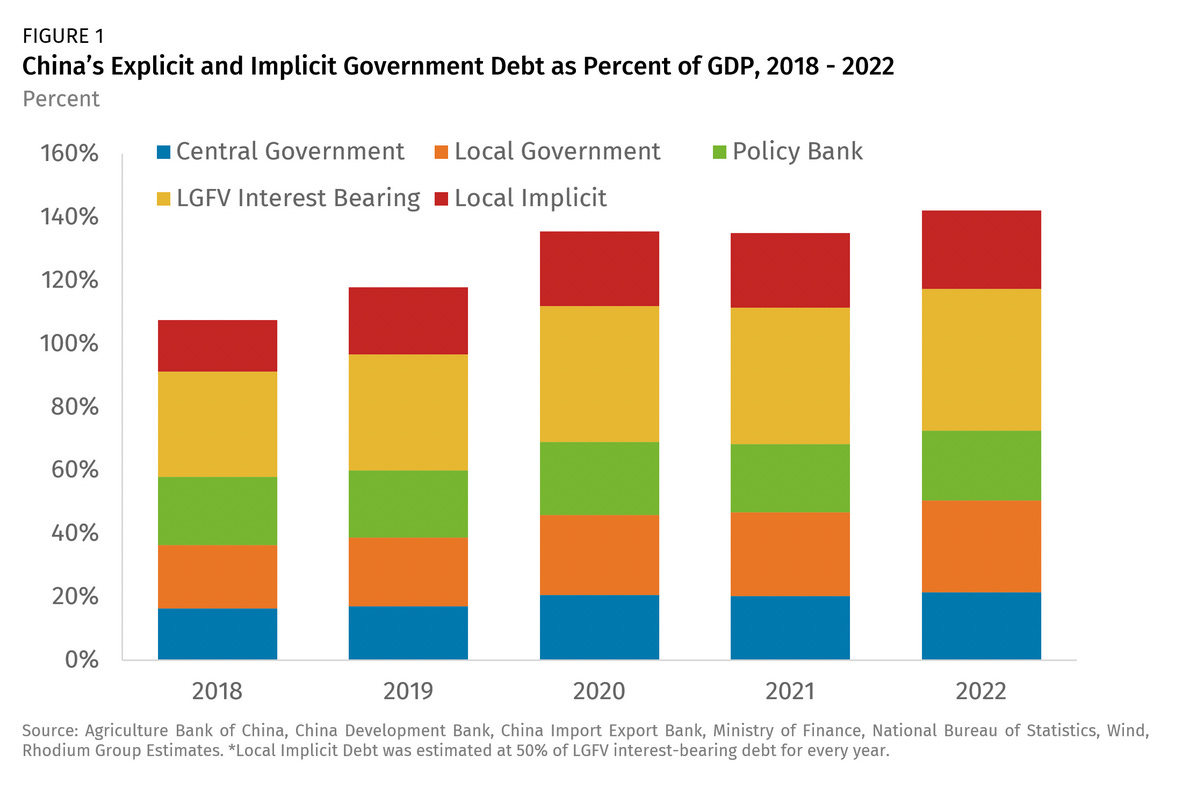

But another, equally plausible theory, is that Beijing doesn’t want to step in because it has realized its own budget might not be able to handle the inevitable wave of local-government failures. In a new report, Rhodium Group examines the breakdown of the national budget vs. local governments and finds that Beijing’s pockets might not be as deep as many assume.

The problem, according to Rhodium, is that Beijing’s debt might be low now—only about 21% of GDP compared to a U.S. federal debt nearer to 120%. But it would balloon to almost 140% if it had to step in and assume local-government debts.

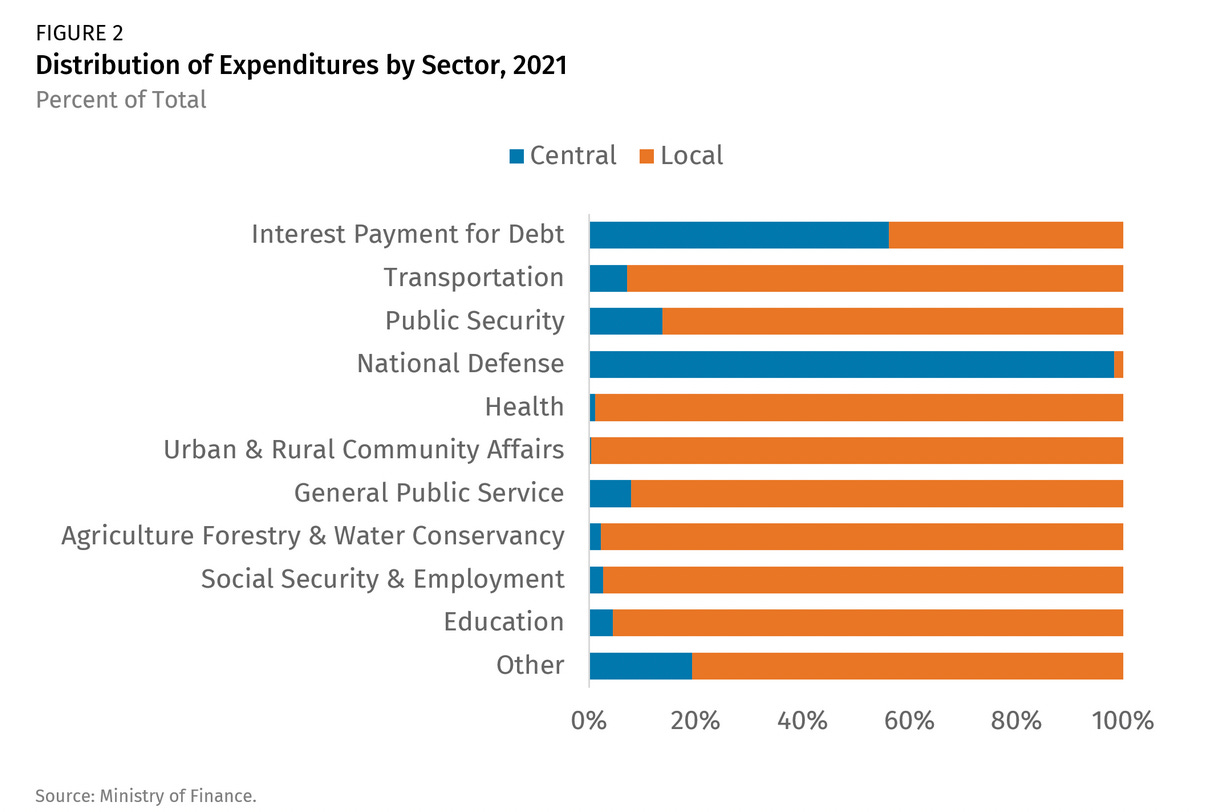

And if local governments go broke, Beijing will also have to step in and pay for all the public services they now deliver, including public transport, schools, and healthcare. In China, local governments shoulder the burden for most every public service. Beijing handles almost nothing but national defense.

But the tax base to support those public goods is low and shrinking. Despite being a Communist country, China’s tax revenues are only 14% of GDP, compared to an OECD average of 34%. That isn’t entirely intentional: Beijing has limited local governments to relying on value-added taxes and corporate income taxes, both of which tend to fall when the economy slows. Local governments resorted to land sales and borrowing against their land holdings, the results of which were catastrophic.

To fill the gap, Rhodium argues that Beijing would likely have to boost taxes on consumption and personal incomes, something it doesn’t want to do as it tries to replace the economy’s reliance on investment with consumer spending.

And it’s also likely to have to roll back its larger policy goals to take on domestic spending responsibilities. That means lower military spending to achieve China’s aspirations as a global superpower.